A resort island in the East China Sea became a magnet for Yemeni refugees fleeing civil conflict.

When civil war erupted in Yemen in 2015, it caused barely a ripple half a world away in South Korea. In Seoul, they were focussed on North Korean missile tests and a free trade deal with China. As 2016 rolled around, a monumental corruption scandal was unfolding that would eventually send president Park Geun Hye to jail for 24 years.

Amid this political turmoil, nobody noticed the 2016 arrival of seven Yemeni asylum seekers on Jeju, a South Korean resort island an hour by air from Seoul. In 2017, the number of Yemenis arriving on "the Hawaii of Korea" had grown to 42, still with minimal coverage or concern.

Then in 2018, Jeju became the focus of sudden and agitated attention for South Koreans as the resort island's Immigration and Foreign Affairs Bureau reported 561 Yemenis had entered the island in the first half of that year.

Hamza al-Odaini, 17, looked at a map of the world to see where he could flee without applying for a visa.

As the Yemeni arrivals surged, the government imposed a ban (on April 30, 2018) on their travel to the Korean peninsular, restricting their movements to Jeju island.

Like Australia, with its controversial offshore detention policy, the South Korean government responded to the sudden increase in asylum seekers by restricting their access to the "mainland".

South Korea is one of the few countries in Asia which is a signatory to the 1951 Convention on Refugees but has been cautious in acting on its commitment. It signed up in 1992 but did not recognise its first non-North Korean refugee until 2001. It was another nine years before citizenship was granted to a recognised refugee.

"The restriction gives the perception that refugees are someone to be locked up," said Jeon Soo-Yeon, a lawyer with the Public Interest Law Centre appeal. "I think that maybe the government is using the media to cultivate anti-refugee sentiment in the public."

On June 11, 2018, the South Korean Ministry of Justice doubled down, issuing special restrictive employment permits to Yemenis which limited their right to work on Jeju to those sectors in need of extra labour: aquaculture, fishing, and restaurants.

***

HOW and why had Jeju become such a magnet for Yemenis fleeing the ongoing civil conflict? It was a confluence of factors, involving visa waiver programs in two countries and a budget airline.

Seventeen-year-old Hamza al-Odaini told The South China Morning Post he looked at a map of the world to see where he could flee without applying for a visa. Yemenis saw they could escape to Malaysia, another Islamic nation, and stay for 90 days without a visa. And, since 2002, South Korea's Jeju island had also had a 30-day visa-waiver program. It allowed visitors from all but a handful of blacklisted countries to visit, visa-free, in an effort to boost the island's tourism industry.

Then, in December 2017, budget carrier Air Asia provided the final link. It introduced a direct flight from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to Jeju and a visa-free pathway from war-torn Yemen to South Korea was opened.

With the sudden increase in Yemeni arrivals, public opposition bubbled up. A petition calling for the Cheong Wa Dae (The Blue House) presidential office to abolish permits for asylum seekers easily exceeded the number of signatures required for consideration.

A group called People's Action Against Refugees, opposed to the arrival of Yemeni asylum seekers was formed and used coded language to stoke islamophobia in the community.

"Most of the Yemeni refugees in Jeju are young Muslim men. They are dangerous because they have a low awareness of women's human rights and live in a Muslim way of thinking," a spokesman for the anti-refugee group said at the time. "They flew through Malaysia to this faraway country. That means they are rich. The real refugees remain stranded in the country. The Yemeni refugees are not here for a pure purpose."

However, Park Yo-sep, a reporter with a Jeju newspaper challenged the claim. "There are no clear statistics on the correlation between [the Yemenis] and crime. Foreign crime statistics show no evidence of a high crime rate by Muslims. Statistics show that crime rates by foreign tourists are the highest."

The People's Action Against Refugees spokesman also focussed on the financial benefits, saying would-be refugees were receiving 537 won per month for the first six months. "After that, you can get a job. There are total of three stages of refugee litigation, and even if the final decision is not approved, you can return to the first round of cases. That's how they keep living in our country," he said.

Jeon, of the Public Interest Law Centre said, "There are worries about Yemen refugees because they are Muslims. There always exist extreme forces in any religion. Rather, refugees in Korean society are very careful about their actions."

"South Korea has 500 [Yemeni asylum seekers] compared to 50 million people ... it is unlikely that our country will change easily into a country with a lot of refugees."

Surprisingly, given international critique of Australia's treatment of refugees on Manus and Nauru, Korean refugee advocates hold up Australia's template for processing asylum seekers as far better than their own.

Jeon said there are only 30 translators in Korea to help the Yemenis prepare their documentation. "Due to the lack of manpower, the process of preparing the draft is very urgent and there are many mistakes. This unfair screening process is the biggest cause of refugee refusal."

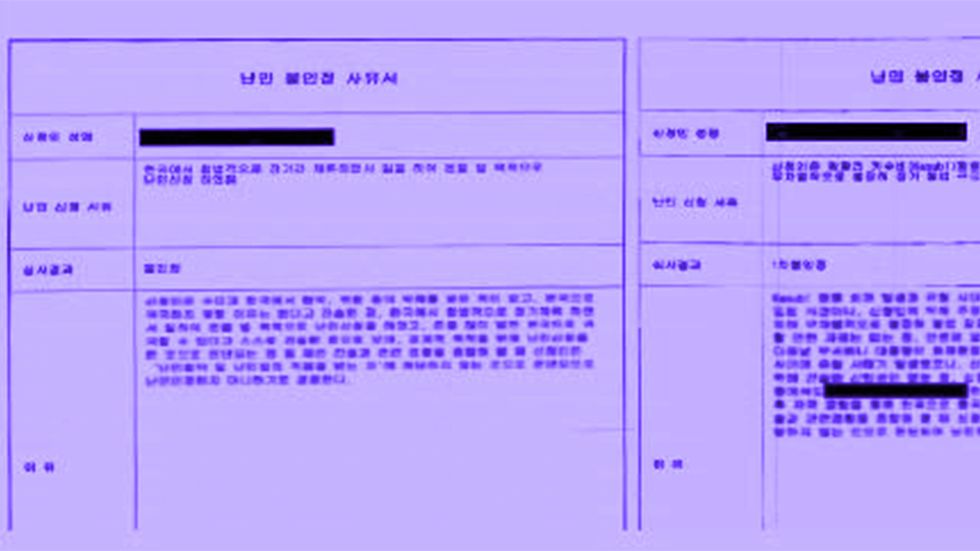

In Australia, the refugee refusal letter is issued in a 200-page professional report and translated and delivered in a language that the applicant can understand, she said. In Korea, about half of the A4 pages are in Korean, which the refugee applicants cannot read, and use an almost identical wording.

"We should discuss how they can integrate into Korean society without any problems and live their lives as human beings, rather than [developing] a policy of limiting and regulating them."

As of December 2018, of 484 Yemenis who applied for refugee status on Jeju: two had been approved and a further 412 given a lesser humanitarian stay permit; 56 received a non-authorisation and 14 got a termination when they withdrew or left the country.

For the Yemenis on Jeju, their future remains uncertain. However, one thing is clear - the door to further Yemeni arrivals has been closed, simply and clinically. By adding Yemen to the short list of countries whose citizens are denied access to Jeju's visa waiver program, South Korea, a signatory to the Refugee Convention, has "solved" its Yemeni refugee problem.