In a fiercely competitive job market, close to 2 million students in Maharashtra, the epicentre of COVID-19 infections in India, have had their future career plans put on hold.

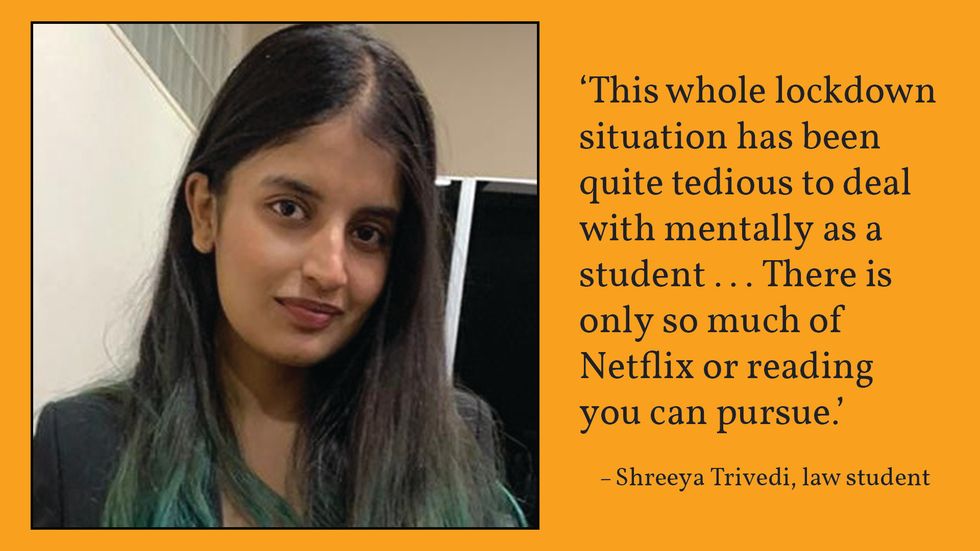

The call from her parents was insistent: "Come home now." Shreeya Trivedi remembers quickly packing her bags, as she fled her apartment in Mumbai and headed home to Nagpur.

Trivedi, 22, a student at the city's prestigious Government Law School, was alone in the apartment, her flatmates having already left town. From early on, Mumbai, the densely populated commercial capital of Maharashtra state, was the epicentre of the India's virus outbreak and her parents feared it would only get worse.

"I remember packing my bags hurriedly, bringing the bare minimum with myself and coming back to Nagpur … where the situation was rather better, with only a handful of patients infected," she said.

Five days later, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi called for a national "People's Curfew" from 7am until 9pm on Sunday March 22. The one-day experiment put 1.3 billion Indians under a 14-hour shutdown order. It was voluntary. When Modi announced a national 21-day shutdown two days later, it was mandatory.

Across the country, Indians of all socio-economic classes were caught in the same mad rush to get home. Under the March 24 shutdown edict: all travel services including international and interstate buses, railways and flights were banned, all commercial outlets and organisations were shut down, effective immediately. Education institutes were closed, and all the ongoing exams were halted or postponed. Only the essential goods and services, like grocery shops, hospitals, medical stores, banks, police stations and fire services, were allowed to operate.

'The middle class will survive this but the poor will die ... in countries like India, the poor ones die first.'

Tens of thousands of migrant workers jostled for buses, shoulder-to-shoulder as they raced to escape the cities and return to their villages.

Tens of thousands of university students found their institutions closed down, exams postponed, futures uncertain. There are more than 4600 colleges affiliated to 44 universities educating 1.95 million students in the state of Maharashtra alone. Many of these students attend colleges away from their hometowns.

Shikha Chaurasia, 20, a journalism student studying in Pune, Maharashtra state, recalled the speed with which it took hold. India's first known coronavirus case was recorded on January 30, in the southern state of Kerala. The patient was an Indian student who had returned from Wuhan, China where the virus originated. After that first reported infection, "soon the virus began spreading to each and every corner of the country".

She was aware of the international news coverage of the virus's spread from China to parts of Asia to Europe, yet, when India's shutdown came, she wasn't fully prepared for the comprehensive restrictions. As the lockdown was imposed, Chaurasia attempted to leave Pune and return to her hometown of Nagpur, 700 kms to the east. She discovered all travel services - planes, trains and intercity buses – had been banned until further notice. She opted for what she could get, one of the last local buses to nearby Aurangabad, where she had relatives and the COVID-19 situation was relatively better than in Pune. And in Aurangabad she has stayed.

Seven weeks and three rolling lockdown phases later, the shutdown remains largely in place, with citizens locked down wherever they were on the day it was enforced.

"I am currently stranded here since [March] and there is no way for me to travel back home till the lockdown and travel ban is lifted," she said. "I was also supposed to graduate in the month of June this year, but all my exams and the convocation ceremony have been postponed and now, several of my classmates and I will not be able to graduate. As a result, it will be more difficult for us to find jobs or internships after the lockdown is over."

Law student Trivedi did make it home to Nagpur before the shutdown but had expected to be there only a few days. "It's been almost a month since I got here, and the number of patients only seems to be increasing. We often seem to run out of the basic food items and necessities because we made sure we wouldn't hoard," she told Newsworthy, by email in April.

The student would normally have plenty of course reading for her law degree to fill her time. "The semester had just started... I came back without any books because I did not anticipate the lockdown to extend. So here I am, a helpless law student without any books, struggling to study everything off the internet." A distinctly Indian middle class problem.

Different strata of Indian society are impacted to differing degrees. Mandar Pande, 20, a finance student in Nagpur put it bluntly: "The middle class will survive this but the poor will die. Like in war, the front-line troops die first, similarly, in countries like India, the poor ones die first."

"I see my apartment's watchman who doesn't earn much and has a family to take care of, and in this lockdown situation he isn't able to provide much food for his family. Now, him being the only person earning in the family, he has to risk his life every day to come to duty and earn some money."

Pande also sees the impact on the streets devoid of people. The street dogs which survive on the scraps thrown their way are slowly starving to death.

"The situation of animals on the street is getting worse day by day, due to scarcity of food," Pande said. "Before the pandemic, people used to throw food remains which used to feed them. Presently, everyone is indoors and preserving whatever they have, which leads to minimum waste because of which stray dogs and cats are not getting enough to eat." He tries to feed them at least twice a day, but the scarcity of resources has made it extremely difficult.

****

India had a steadily climbing 81,000 positive COVID-19 cases by Friday, with more than 2,600 dead. (By comparison, the United States, with a quarter the population of India, has 86,000 dead.) Beyond the COVID-19 infected, millions more are impacted by the circumstances. While restrictions have been softened in some areas less affected by the virus, there is no certainty as to when the lockdown will end. On Tuesday, India's rail network cautiously stirred back to life. The prime minister has announced a US$260 billion (A$404 billion) economic recovery package and asked each state chief minister to provide a broad strategy by Friday, May 15, on how their states will end the lockdown.

"The lockdown has affected a lot of sectors and people of all strata.," said journalism student Chaurasia. "The students who were appearing for national and international level exams could not do so, and their admissions are on hold. Daily wage workers and labourers are left with no income and have to battle for everyday necessities. Housing societies are sealed and strict rules and guidelines are imposed on the residents."

"We are eagerly waiting for the situation to cool down and for the life of every citizen of India to go back to normal," she said, echoing a sentiment familiar around the world.

In Maharashtra, government servants have gone door-to-door for a "COVID inspection" in some areas. When they knocked on the Trivedi door, "we were asked questions related to travel history, health and diseases, and basic general information … This feels like a step in the right direction to curtail the spread of disease."

Despite the necessity, like students the world over, Trivedi is over it. "This whole lockdown situation has been quite tedious to deal with mentally as a student and in general too. There is only so much of Netflix or reading or hobbies you can pursue. But it is imperative that we follow the rules and try to flatten the curve."

****

What will stay with them from this strange time?

For Pande, it is a stark memory that came during the first voluntary 14-hour lockdown on March 22. "I will always remember this lockdown story… the Prime minister asked the public to clap hands and ring bells during Janata Curfew (people's curfew).

"Many of them got out of the house, took to marching, dancing, clapping, covering entire roads … They fought against COVID-19 by doing the exact opposite of what they had been told to do, [which] was to be locked down in their houses for the entire time. It was like they were celebrating a birthday party. The police had to intervene and restore equilibrium."

For Trivedi, it is the birthday party that wasn't, coming as it did just days after Phase 1 of the rolling national lockdown was announced. "On the day of my birthday everything was fully shut down and the whole country was at a halt. So much so that I couldn't even get a cake for my birthday … I'm sure I'm going to remember this birthday for the rest of my life."

For Chaurasia, the pandemic has "drastically modified" her perspective on many things. It has opened her eyes to the fact that "poverty is the most sorrowful problem a country could have".

"Every citizen in India who is in the comfort of their home is realising the dignity of labour and have started to respect the poor workers who sweep the streets, clean our surroundings and homes."