Science is uncovering what influences an umpire's split second decision-making and why our brains struggle to follow a 'spinny' ball.

In Brisbane, Australia’s women’s cricketers have been ramping up their preparations for this month’s Ashes tour by playing the Australia A squad. Behind the scenes, another less celebrated group will be carefully preparing for the upcoming English season of women’s and men’s Test and T20 cricket — the umpires.

One who understands that pressure and preparation is Joshua Adie, a cricket umpire, based in Brisbane, for the Australia’s Women’s National Cricket League and the Women’s Big Bash.

Adie and I have met to talk about how things have changed in the world of cricket. How the rise of social media has brought new levels of scrutiny to the game, how science is uncovering the influences of umpire decision-making and how the industry is hungry for young diverse talent.

Adie, 28, is the second-youngest member of the Queensland Cricket Umpires and Scorer’s Association, and as well as umpiring women’s cricket, he recently worked as fourth umpire for the Men’s Big Bash, as well as on field umpire for the Under 19s Ashes. He is also an academic at the University of Canberra.

“I did my PhD on cricket umpire decision making, which is a bit ridiculous,” he said. Technically, he’s Doctor Joshua Adie but to his fellow umpires, Josh is just fine. Adie explained he had no chance as a kid, his family were cricket mad. “My dad and my grandpa are big cricket tragics. I think I went to my first test match when I was three, at the Gabba.

He grew up playing junior cricket but when, at 19, he tore his posterior cruciate ligament and was told he would not play for six to 12 months, he did an umpiring course to stay connected to the game.

“I realised very quickly that I'm a much better umpire than I ever was a player.

“I'm very weird, in that I actually wanted to be an umpire when I was a kid. I used to watch the TV and practise the signals. I'd watch with a score book in my lounge room,” he recalled. Years later, as Adie was learning to umpire for real, he was studying psychology at the University of Queensland. He took a course called “The Science of Everyday Thinking”, a unit on judgment decision making and why people make bad decisions in certain situations.

“At the same time going through my cricket umpire training, there really wasn't any of that sort of level of detail. You get your little blue book of laws. And then you go out on the field and there's no real psychology of officiating taught to you from the start.”

'People seem to be able to understand that this pitch was really hard to bat on. But they never think it’s really hard to umpire.'

Adie found literature on the topic in other sports — rugby, soccer, hockey — but the studies focused on decisions made regarding infringements. In cricket, umpires must decide if a player is out or not out, which Adie felt was a very different type of decision. That led him to think “Maybe I should do this as a PhD?”.

“Thankfully, there were academics in Brisbane who were crazy enough to think that that's a good idea,” said Adie, who subsequently got to watch a lot of cricket and interview his heroes. His thesis was titled “When in Doubt, it’s Not Out! Leg-Before-Wicket Decision-Making in Elite-Level Cricket Umpires”.

“First thing we found is that generally umpires are conservative, which sort of makes sense. They are more likely to say, ‘not out’ than ‘out’.” Being conservative, he said, is a crucial part of umpiring. “You can have good decisions. You can have bad decisions. You can have correct decisions and you have incorrect decisions.

“You've given someone ‘not out’. You thought maybe they hit their pad. [But] there was enough doubt for you to say ‘not out’. DRS [decision review system] tells you that you're actually incorrect. But it was still a good decision because you made the correct umpiring decision based on the information you had in that moment.”

Adie’s study also found that conservatism increases in Big Bash compared to Test Cricket. “They're saying, ‘not out’ in times when they should be saying ‘out’. We don't have a real definitive reason why that might be. Potentially there's so much more scrutiny on officials in the Big Bash from the media, from spectators, from the general stakeholders,” he said.

I ask Adie if the increased reliance on the DRS and the rise of social media has increased the scrutiny placed on umpires. “It's sort of feels like it's gone up a notch.

“You make one decision that someone doesn't like, then suddenly, there's going to be conversations online, whether that's from mainstream media, or comments on social media,” he said. Back in March, when the Australian men played India in the Indore Test, there was immense scrutiny from viewers over umpires decisions, even prompting commentators Mark Waugh and Brad Haddin to accuse the umpire of rigging decisions, on-air.

“They're playing on these pitches that spin a lot. From an academic perspective our brains are really bad at following changes in direction. That's why batsmen get out on spinny wickets. People seem to be able to understand that this pitch was really hard to bat on. But they never think it’s really hard to umpire.

“They're okay when their players make a mistake. It might be disappointing, and you might be annoyed for a bit. But if an umpire makes a mistake, they don't give you any leeway. It's never this fallible person in a high-pressure environment. They think that you're a pushover or you're incompetent.” And laughingly: ‘Or you're a shithead!”

I ask Adie if that pressure takes a mental toll “Absolutely. For me, there's definitely times where you've given it your all. You've tried really hard, you've done all the preparation you could and then you just have a bad day on the field. No official goes on to a field, gives up their time, often volunteers or paid fairly poorly, to do a bad job.”

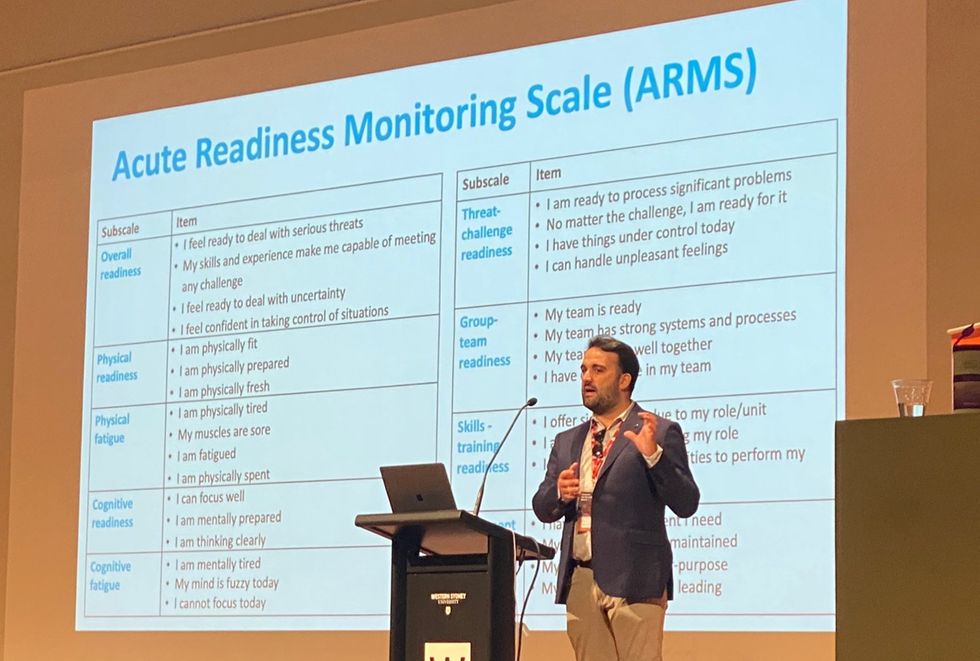

Adie said his research has made him a “self-reflective” umpire. He’s now considering how his findings can be used to train others.

“I'm working on a project with some collaborators in Victoria and in Scotland. We're looking at talent identification in sports officials. How you identify people who are going to be good. How you then develop them.

“There's been a real shift in, at least in my experience, in sports officiating. Away from ‘Well, back in my day, this is how I made decisions’ to ‘Okay, here's what the evidence says. Here are some strategies that you might need to implement’.”

However, it is difficult to recruit new umpires. “It’s a real struggle to get young people to transition from playing,” he said. “They don't see themselves wanting to stand on the field all day. It's really hard to convince people that it's a good idea.”

At present, cricket umpiring remains a male-dominated profession. I ask if Cricket Australia, as well as the state panels, need to do more to recruit more women. “I think it'd be silly not to.”

“In Australia, we've got on our national supplementary panel two excellent umpires who happen to be female. We will start to see women taking up umpiring in Australia because they see Eloise Sheridan and Claire Polosak not only getting a go in on the national stage but doing a great job,” he said.

Adie explained the job is often a labour of love. He calls it “work-life-cricket” balance. “It really takes it out of you. For me to have gotten where I am, a lot of it has to do with having a supportive partner. A boss at work, who can see that there's some potential in this for me.”

Even Adie, who is a semi-professional umpire, still works as an academic Monday to Friday. “A lot of the current national umpires haven't given up their day job. There's a couple of policemen, school teachers, lawyers. Because generally, if you get onto the national panel, you're really lucky if you stay on it for more than four years.”

In his nine years as an umpire, Adie has witnessed the rapid rise in the quality and depth of the women’s game from up close in the centre of the pitch.

“When I started umpiring the women's grade cricket competition. When the state and national players weren’t there, the quality of the cricket dropped dramatically,” he recalled. “But then over the last few years, they've started properly televising the women's Big Bash. And what we're seeing is young girls taking up cricket earlier in their life. They're seeing these role models on TV, they're taking up cricket earlier, and by the time they get to the women's grade cricket competition they're quite skilled.”

This month, Australia’s women head to Europe as the World No 1 ranked team in One Day and Twenty20 cricket. No doubt Adie will be watching. I ask what he likes more, cricket or academia. Adie struggles to choose one. “I think for me, the way I've always thought about officiating is, as soon as it starts to feel like it's actually a job, is probably when I'm going to pull the pin. Right now umpiring is what I do do fun” Something tells me that even if he one day hangs up the white hat, he’ll never stop practising his scoring from the lounge room.

Maddie is a journalist, podcast presenter and playwright. She completed her Master of Journalism and Communication degree at the University of New South Wales with a High Distinction and was awarded positions on the Faculty of Arts, Design & Architecture Dean's List in 2022 and 2023. As a playwright she has written for Queensland Theatre, La Boite Theatre Company, Dead Puppet Society and Screen Queensland, and has directed for La Boite Theatre Company and The Good Room.