Teeth can affect our mental health, physical wellbeing, even our job prospects. So, what happens to young Australians who can’t afford to take care of them?

When Hannah Fowler was a 21-year-old university student, her dentist recommended she have her wisdom teeth extracted. The procedure was quoted at upwards of $6000 and her financial circumstances left her unable to pay the dental fees.

She was juggling full-time study with casual work while living independently in Perth. “I haven’t really had much money because I’ve had to take care of myself since I moved out of home when I was 17. So, spending six grand wasn’t even in the picture,” Fowler said.

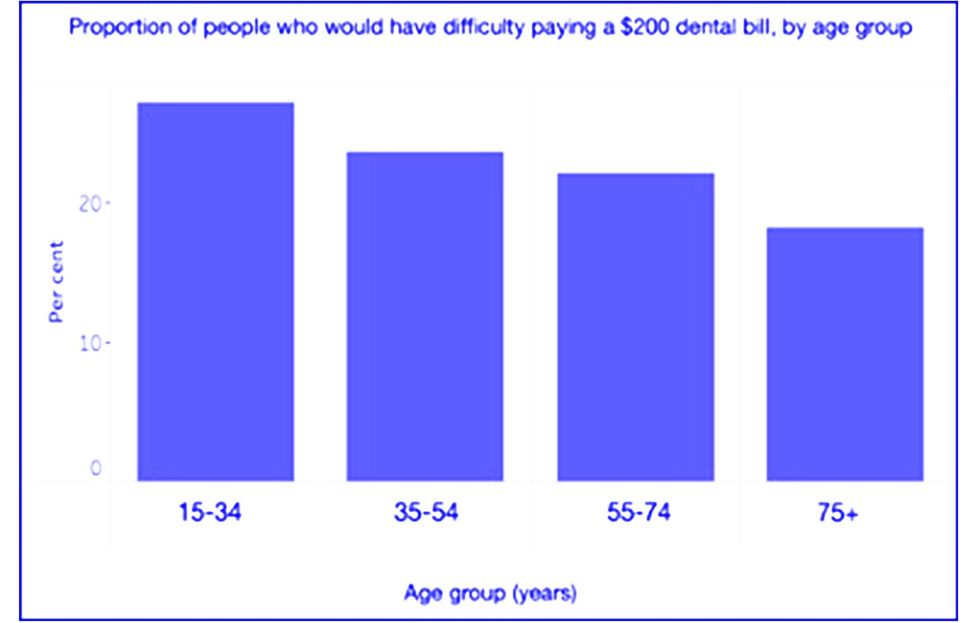

She is part of a growing younger generation grappling with dwindling incomes, underemployment, higher costs of living – and dental costs. A 2017-18 national study found people aged 15-34 were most likely to have difficulty paying the average $200 dental bill, which is excluded from Medicare. That exclusion has made good oral health a luxury many cannot afford, with the bite of dental inequality especially sharp for young generations.

Knowing that fully erupted wisdom teeth cost less to remove, Fowler waited for them to grow through her gums, a slow, agonising process spanning five years and three infections, which cost $1200 to treat – before extraction surgery.

“I couldn’t afford to get my teeth taken out until this year … I had five years of teeth pain that I just had to ignore,” said Fowler, who is now 26 and living in Melbourne.

Like 40 per cent of young Australians, Fowler delayed her dental care due to the cost. This can trigger systemic infections that lead to greater long-term expenses, compounding the inequalities faced by vulnerable youth, such as those navigating chronic or mental illnesses.

Due to the costs of managing their chronic illness, UNSW student Chantel Henwood must frugally prioritise health expenses. It’s a balancing act burdened by the cost of dental care. “I’ve needed fillings for at least four years, but saving as a student is challenging … and my medical expenses are already huge,” said Henwood.

“Dental often falls behind when it’s competing with medication, physiotherapy, and mental health – but this isn’t because it doesn’t cause me problems.”

Henwood’s naturally overcrowded teeth cause severe migraines, jaw pain, and toothaches that make eating uncomfortable. They must be selective with food and where they chew – sometimes skipping meals to avoid the discomfort. These behaviours are particularly harmful to Henwood, who is neurodivergent with a history of eating disorders. “Any stress surrounding food can often exacerbate surrounding challenges with mental health,” they said.

On top of this, people with mental health disorders face greater risk of developing costly dental problems due to the side effects of some anti-psychotic and anti-depressant medications. This is particularly worrying for young Australians, who are more likely to experience mental health issues than their older counterparts.

Chris Lee, not his real name, a 23-year-old Canberra resident with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, said his medications have caused “so much grief” in oral problems and expenses. He experiences common side-effects like painful teeth grinding and "dry mouth" that causes “humiliating” bad breath. He has spent $800 on an occlusal splint (a custom dental guard) to protect his teeth from damage and buys specialist mints, mouthwashes, and lozenges to relieve mouth dryness.

“It sucks that to feel like a functioning human being through medication, you have to make other sacrifices [in oral health],” Lee said. “It’s not just ADHD – antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications also have oro-facial side effects that significantly increase risk of dental problems.”

In addition to whether they can afford dental health, young people are also constantly confronted, via social media, with gleaming, perfectly formed influencer smiles. Crooked or discoloured teeth (whether caused by genetics, malnutrition or poor oral habits) can significantly damage self-esteem and emotional wellbeing.

This rings true for Angie Gil, 22, whose “naturally uneven teeth” shattered her confidence and impeded her social interactions for several years growing up in Taree on the NSW mid-north coast. “My parents couldn’t afford to pay to get my teeth fixed when I was little,” she said. “I obviously couldn’t afford braces or veneers at a younger age either … I was so insecure about [my teeth] for so long.

“All of my friends had parents who spent thousands of dollars on their teeth, whereas I didn’t have that option. It led to me feeling left out … I very rarely smiled with my teeth in photos. Even when I laughed, I would cover my mouth,” Gil said.

So extreme was Gil's insecurity that when she could finally afford treatment, she spent $3000 on cosmetic veneers – forgoing the seven fillings recommended by her dentist.

“I can’t afford to do both…so I preferred to get cosmetic teeth, as that benefits me more emotionally and mentally than fillings would,” she said.

People with straight, white smiles are perceived as more attractive, intelligent, and employable than those with crooked or decaying teeth, according to a paper published in the Medical Journal of Australia. These judgements can harshly impact young adults – a socially active demographic at the cusp of starting their careers. Additionally, the stigma towards dental defects can further isolate disadvantaged youth who lack the education and resources to improve their hygiene and appearance.

So, who is responsible for our teeth? Ahead of Saturday's Federal election, neither major party is willing to commit to funding universal dental care. The Greens have announced a $77.6 billion plan to integrate dental services into Medicare.

“In a perfect world, I would love for all dental care to be covered [by Medicare]”, said Lee, but he also recognises the need for personal responsibility over our teeth.

However, he says that “someone eating a poor-nutrition diet and using the cheapest toothbrush because they have lower socio-economic circumstances is going to be inherently disadvantaged when it comes to maintaining oral hygiene.”

Thus, he wants the incoming Federal government to prioritise equitable preventative measures instead of reactive treatments. This includes providing early dental education and subsidised oral hygiene products for people with low incomes or disabilities.

As a Health Promotions Officer for their university, Henwood also champions universal dental care – especially for young people. They say that this curbs the growth of severe oral issues that later strain the public healthcare system.

“Having dentistry included in Medicare ensures access and preventative care. Prevention is always better,” they said. “Every single person needs dental care at multiple stages in their life... it’s absolutely insane to me that dentistry isn’t already covered in Medicare.”

Afraid of an egg: the tyranny of living with social media's body standards