'It is better to risk saving a guilty man than to condemn an innocent one,' said Voltaire. Here are the stories of two 'condemned' men who walked free – eventually.

JOHN BUTTON

SUBIACO, WESTERN AUSTRALIA

February 9, 1963

THEY went about a mile and she still would not jump in the car. John Button says he tried in vain to make amends with his girlfriend after they fought that night, on his 19th birthday. He drove along beside her, calling: "I'm sorry. I apologise. Will you hop in the car and I'll drive you home?"

"NO."

The events that followed that teenage misunderstanding would change 19-year-old Button's life forever, they would end girlfriend Rosemary Anderson's life at 17 and impact across the decades on their siblings, partners and children. If the birthday boy had not stopped for that cigarette, for a brief minute, maybe none of what came next would have happened.

That evening, in the comfortable middle-class Perth suburb of Subiaco, Charlie and Lilly Button went out, leaving their son John, his younger brother Jimmy and John's girlfriend Rosemary at home at 8 Redfern Street. After buying fish and chips, the three teenagers sat glued to the television screen as they ate their meal. When somebody pinched a piece of John's snapper, he assumed, wrongly, the thief was his little brother and called Jimmy a few choice words. But it was Rosemary. Thinking her boyfriend was saying those words to her, she became upset. "If you're going to be like that," she said, picking up her handbag, "I am going home."

She started walking down the street in the direction of Mount Claremont, an adjacent suburb. Button followed in his car. However, when several attempts to make it up to his girlfriend failed, he stopped and lit a cigarette, watching as she walked through a darkened railway underpass and turned left onto Stubbs Terrace, disappearing from sight. He thought that after walking through the underpass, she might be more inclined to accept his lift home and drove after her again.

As he learned many years later, as Anderson turned into Stubbs Terrace, Eric Edgar Cooke drove down the street in the other direction, saw her, did a U-turn, and came up behind her with the intent to run her down, before fleeing the scene.

Minutes later, Button would find his girlfriend lying in the sand, bleeding and unconscious, with a grievous head injury. Overwhelmed by fear and panic, he picked her up and drove her to her doctor in Mount Claremont. He would never see her again.

From there, the police took him away for questioning, and when he emerged from the interrogation, he had been charged with the wilful murder of Rosemary Anderson, the woman with whom he had wanted to make a life. This account is set out in investigative journalist Estelle Blackburn's book on Button, Broken Lives (Hardie Grant 1998), and by Button himself in an interview with Newsworthy.

'It's like being kidnapped by society for years and when you return ... nobody welcomes [you back]. You're a victim, but nobody sees you that way.'

Button would later claim, in his emotional, self-published autobiography Why Me Lord!, that Detective Sergeant John Wiley (the senior of two policemen on the case that night) punched him to get what he wanted. After several hours of interrogation, during which he was not informed of his rights or allowed to contact anyone, he learned that Anderson had died from her injuries. At that, Button recalled, he simply stopped struggling, went to the toilet to vomit and signed the confession that the detectives had written for him.

Devastated, desperate, and hoping for only one thing: to get out of that hellish place, he confessed. His admission of guilt, read in part: "Rosemary was walking on the left-hand edge of the road close to the edge of the bitumen. Before I realised what had happened, I had hit her with the left-hand side of the front of my car. When I hit her, I felt a loud crunch and I carried her a few yards on the front of my vehicle."

****

DECADES later, investigative journalist Blackburn would re-examine the case at the behest of Button's younger brother Jim. In her book Broken Lives, she explored new evidence on police practices and how they had contributed to what she argued was a miscarriage of justice in the Button case. The book, published in 1998, won the West Australian Premier's Literary Award in 1999 and in 2001, Blackburn was awarded the Walkley Award for Most Outstanding Contribution to Journalism.

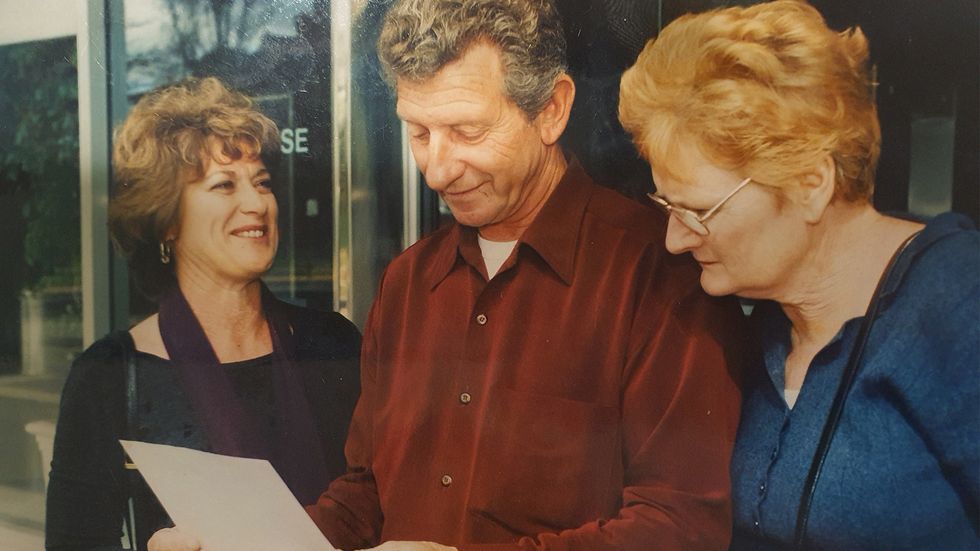

The book led to renewed public interest in Button's case and a successful application to the Western Australian Attorney-General for a new trial. A 2001 retrial in Western Australia's Court of Criminal Appeal, found in Button's favour and his conviction was quashed in 2002. The exoneration was a long way from the death penalty Button would have faced had the jury found him guilty of wilful murder in 1963. Two of the 12 jurors had baulked at a wilful murder conviction and he was convicted on the lesser charge of manslaughter and sentenced to 10 years behind bars with hard labour.

Button didn't appeal his 1963 conviction or sentence as his lawyers advised it could go the other way and he'd find himself convicted of wilful murder in a second trial and facing execution. He would serve the first five years within the five-meter high walls of Fremantle Prison, a maximum-security fortress built by the English and Irish convicts in the 1850s, and the second five years on parole.

ORANGE, NSW

I MEET John Button on a sweltering weekend in early October. Grey-haired. Icy blue eyes. He's wearing an indigo and yellow plaid shirt along with black flannel trousers. Born in Britain in 1944, he is now 76 and his wife Helen is 72. The couple live in the small central-western town 255 kms west of Sydney. At the wheel of his old red Nissan, Button does not take his eyes off the road. He drives smoothly while listening to his soundtrack from the '60s. The soft country twang of Loretta Lynn's voice echoes from the speakers.

Is it wrong for loving you

Is it wrong for being true?

Tell me darling, tell me please

Is it wrong?

When he was released on parole at the end of 1967 Button tried to "pick up the pieces again." He and Helen, who had crossed paths before, dated for a while, then married in November 1968. In 1969, they had a son Gregory and in 1974 a daughter, Naomi.

Button believes his past made his kids stronger. Helen explains they "never told them [their father's story] straight out", it came in bits and pieces. "John kept having nervous breakdowns, and they wanted to know why daddy was in and out of hospital ..."

In Why Me Lord!, Button wrote that as he struggled with post-traumatic stress and depression, he was unable to support his family, leaving his wife to work full-time and to look after the children. He is still on antidepressants. Without them, Button says, "I would be in tears at times. I would get very upset". The medication helps him to act normally. And as much as he would like to feel a bit more, he can't afford to go off his pills because his mood might swing too far the other way.

"It is hard." Helen says, recalling a time when a depressed Button had taken the tiles off their roof because the roofer hadn't done it properly. Their son Gregory was eight or nine. "This night we had a terrible weather and John was in the hospital. He wasn't allowed to come out because he was suicidal. The water was cascading down the wall and all over the carpet ... So, Gregory got on the roof, put on that tarp. 'Mummy, hand me another brick. Hand me another brick.' And I really lost it. I really did."

"He put me through hell," she says. The husband nods his head, silent.

For 39 years, Button lived without social respect, regarded by many in the community as a criminal – even after his conviction was quashed. With the children grown, and with five grandchildren, the couple sold their home, planning to move to an outer suburb of Perth. They recall being invited to a community feast hosted by a real estate agent for all those who had sold their houses through the agency that year, little knowing it would bring Button face-to-face with his traumatic past. The husband of Rosemary Anderson's sister was serving the dinner that night, and, Helen recounts, he literally threw a plate at Button. Used to being humiliated, Button didn't even react, she said, just shrugging his shoulders.

Helen, by contrast, was angry. She told herself: "John is a free and innocent man, we've proved it. How long does this have to go on for? I can't live in a state where everybody continually wants to bounce off of him ... under the pretext that an innocent man wouldn't sign a confession."

British forensic psychiatrist Dr Arian Grounds has compared the trauma of false conviction and captivity with post-war trauma but Button sees it differently: "It's like being kidnapped by society for years and when you return ... nobody welcomes [you back]. You're a victim, but nobody sees you that way."

Fighting to regain a semblance of community respect, Button found an important place and voice, advocating on behalf of other wrongfully convicted people.

Then in 2013, came an opportunity to leave the unforgiving landscape of the West. Their son Gregory, an emergency doctor, had moved with his wife and four children to Orange, a regional NSW town, 3600 kms across the continent. He encouraged his parents to follow. Their daughter Naomi, a family therapist, who has always been very supportive of her father and his passion for the pursuit of innocence, stayed in Western Australia where she lives with her husband and baby son.

In Orange, the Buttons live in a modest unit, in a quiet district a few minutes from the city centre. In her kitchen, Helen collects figurines of roosters, hens, and ducks. Their backyard is full of flowers, but also tomatoes, small grapevines, rhubarb and a fishpond powered by a solar panel that keeps the water running. We can hear the birds singing. Equipped with her blue-and-white-checkered apron over her floral dress, Helen is cooking us a divine vegetarian meal. Rarely have I been so well received; they are charming people. On Sundays, the duo usually go to church.

Since they've been in Orange, Button says, things are "very different". Closer to four of their grandchildren, he is more the active grandfather and with a much lower profile, he is no longer fielding phone calls from wrongfully convicted prisoners or going to visit them in prison on weekends. I ask him if he misses it. "A little bit," he responds, with a look full of gentleness. "I still feel I've got a lot to offer."

****

THE impact on family of those wrongly jailed is enormous. Button's parents Charlie and Lilly were devastated by their son's incarceration, eventually returning to Britain. Blackburn says, in her contact with family, brother Jim, who had supported Button through his years in jail, pointed out "all his parents' money was spent on John's defence, so when they died, there was no inheritance for the other three children". it had been at Jim's urging, Blackburn had looked into the case, and her reporting eventually led to Button's conviction being overturned.

Button remembers life in the penitentiary as like "going back to the Middle Ages." He found it very tough, feeling depressed most nights. However, he described himself as "just the perfect prisoner," staying out of trouble and taking responsibility for the manslaughter he had admitted to committing. Because unless you admit to committing the crime, you do not get paroled. "They say you've not repented," he said explaining the phenomenon known as the "innocent prisoner dilemma". "If you keep saying 'I didn't do it,' you're going to stay in jail for the rest of your life. So, what do you do?"

The day he left Fremantle Jail, Button walked up to a door and waited for someone to unlock it. Then he thought: "Oh no. I can do it." He says it took him some time to get used to the routine of life on the outside again. Even now, decades later, he dreams about prison, "being there and pacing the floor". According to his daughter Naomi, that experience in early adulthood stripped him of the confidence to take initiative "because he might get in trouble, he might not be allowed to". She says that even in the simple outing of escorting her mother into the grocery store, he stands back, a little lost and unsure of what to choose.

When his conviction was quashed in 2002, the West Australian State government gave him $400,000. "But then what [Centrelink] did was knocked our pension back by $800 a month," he confides. Helen adds: "We lost that ex gratia payment very fast."

GRAHAM STUART STAFFORD

BRISBANE, QUEENSLAND

Court of Appeal, Supreme Court

October 18, 2019

The Supreme Court of Queensland is an eye-catching glass tower rising up from a green space in the centre of the turbulent city. It's 10:00 am. Lawyers in black robes and archaic white wigs file through the security checks into the tower.

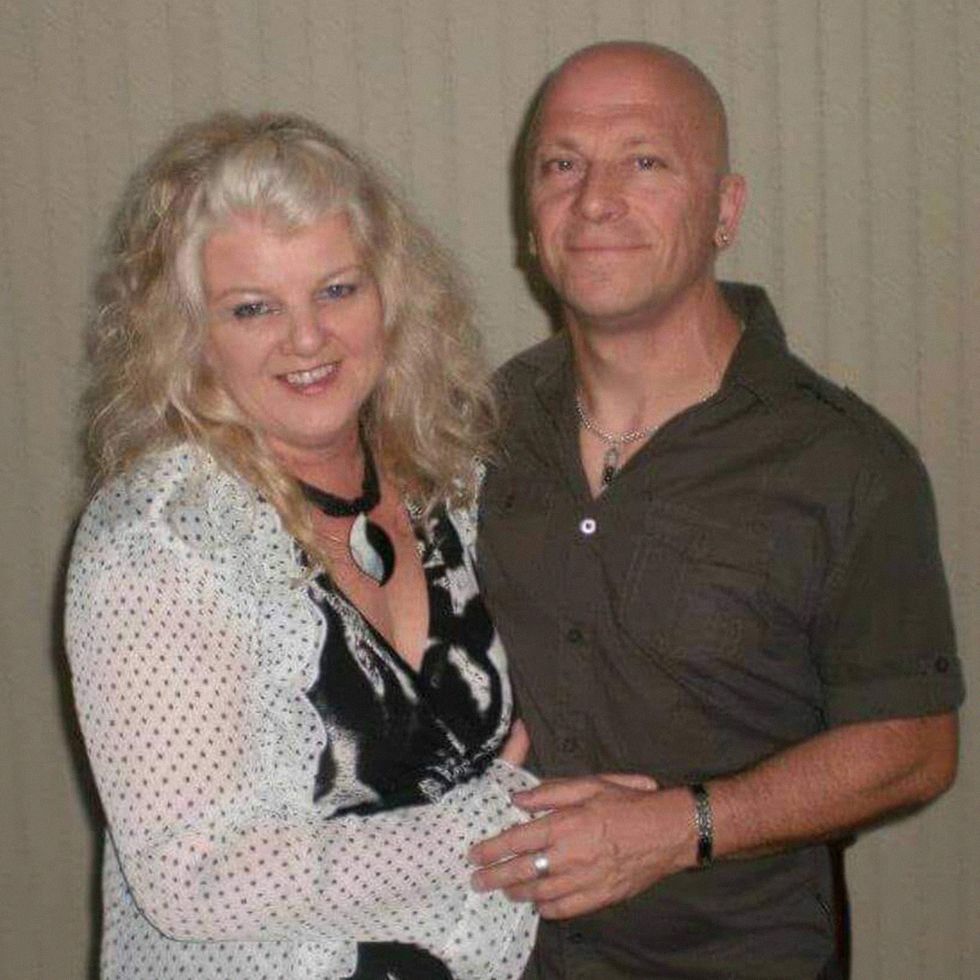

Outside the building stands Graham Stuart Stafford, 56, a short, courteous, iron-willed man. He is bald, with warm blue eyes and wears a casual shirt. He looks a little like Bruce Willis; his face when he smiles gives off a genuine kindness. His girlfriend Jacqueline Welsh is beside him, she's been standing by his side for more than eight years. With blue eyes, highlighted by her matching eyeshadow, her face is framed by long silvered blonde hair.

In 1992, Stafford was sentenced to 15 years to life imprisonment, convicted of the brutal killing of 12-year-old Leanne Holland. The schoolgirl had been missing for three days at the end of September 1991, when her mutilated body was found in the bush at Redbank Plains, close to her house in the outer Brisbane suburb of Goodna. She had been tortured, burnt with cigarettes and perhaps a lighter, and possibly raped, before being beaten to death with a blunt object.

At the time of Leanne's murder, Stafford, then 28, was the de-facto partner of Leanne's older sister, Melissa Holland, and lived with them and their father Terrance. Police argued the former sheet metal worker Stafford was "the last person to see [the little girl] alive," and as such was their No.1 suspect.

In September 2020, almost three decades on, Leanne Holland's murder remains one of Australia's most controversial unsolved cold cases, with many questions still unanswered. Unlike John Button, Stafford did not sign a confession and has always maintained his innocence. He was therefore surprised to get parole after serving close to 15 years, his minimum jail term. He was expecting the usual "you're still in denial [defence]".

His partner Welsh knew Stafford very well prior to his arrest and she knew the local area. "We knew he wasn't guilty because we knew Graham. His morals, his beliefs, his family upbringing, everything. I mean when you know someone and you spend time with them, he's never had any convictions before … And he was in a happy relationship."

"I think a lot of the reason they gave me parole," Stafford says of his release in 2006, "was because they probably agreed with everybody else that this guy has been in all this time, has not shown any ounce of aggression, any ounce of violence."

On December 24, 2009, Stafford's conviction was quashed. However, the Queensland State has never acknowledged he did not commit the crime, nor given him the option for a retrial or an inquest. Initially, a new trial was recommended but on March 26, 2010, the Queensland Director of Public Prosecutions announced such a retrial would not be in the public interest. Next came a two-year police review, completed in 2012, but never released. Queensland Police have refused to share it with him (or to make it public) on the basis of "professional privilege". So, Stafford continues to pursue court action to clear his name.

While the file remains out of reach for Stafford, Channel 7 gained access to the review in 2017 and quoted it saying there was "strong, credible, reliable and admissible evidence implicating Graham Stafford only for Leanne Holland's murder".

That "evidence" has never been tested in court. The media network allowed Stafford's lawyer Joseph Crowley to view the review but not take notes. The "incriminating evidence" in the file, said Stafford's lawyer, included the claim a maggot, similar to those found in the dead girl's body, was allegedly found in the boot of Stafford's car; though no photo was produced nor was it referenced in any police officer's notes. Forensic testing showed the maggot contained no ingested human DNA.

On this day he was in court on an administrative procedure, still seeking access to that two-year police review. In the high-ceilinged court room, Stafford was attentive, leaning slightly forward as his lawyers energetically sought access to the review. Concerned, Welsh's hand was upon his knee. They exchanged looks. The professional privilege is revoked. It is a win! There are other hoops to jump through but he is again moving forward in his stated quest for "truth and transparency" on the part of the institutions that sent him away for almost 15 years.

As with Button, the overturning of Stafford's conviction was largely due to outsiders. In this case, the ongoing efforts of a former detective turned private investigator Graeme Crowley provided new evidence, which in turn exposed the evidence used to convict Stafford as seriously flawed.

Crowley was able to show police had lied, concealing evidence that would have vindicated Stafford. The forensic material doesn't hold up well and a leading forensic expert supported the claim that Leanne could not have been killed in her house, nor be stored in Stafford's shiny red Gemini.

"The police forensic scientist [Dr Angela van Daal] says Leanne wasn't murdered in the house. They know that if she wasn't murdered in the house there was no other opportunity anywhere for me to have done that," said Stafford.

They stated in their files that the next-door neighbours weren't at home the day Leanne disappeared, which was untrue; they had spoken to Stafford, then to Leanne on her trip to the shops from which she never returned.

Crowley's investigations showed the neighbours, and others, were never called to testify on the stand; the alleged murder weapon, Stafford's hammer, mysteriously vanished before his trial; and a "witness" was shown the photograph of Stafford's vehicle before being called to the bar to give a detailed description of it. (The witness claimed to have see have seen the vehicle near the crime scene).

He also found three persons of interest, all with criminal history and in the same geographic zone, only one of whom was questioned by the police at the time. The second, Sean Peter McPhedran murdered another schoolgirl, Julie Ann Lowe, shortly after Stafford's arrest. The third person of interest – Stafford had to hold back tears, his voice breaking as he spoke to Newsworthy about him – was close to the police and followed the investigation.

In 2010, a woman who claimed to be the daughter of that third person of interest, raised the likelihood with The Brisbane Times, that her father had killed Leanne. She said she was "being tortured in similar ways with cigarettes and lighters and the abuse ... it was happening at the same time ... when Leanne went missing, I was being assaulted." She also said her father had shown her a police file containing post-mortem photographs of Leanne, telling her "this is what happens to little girls who don't do what they're told".

****

STAFFORD described his 14-year prison experience as gruesome. In the first year, he was brutalised by inmates, ending up in the emergency room. In prisons there is a hierarchy and those who have murdered or abused a child are on the lowest rung, with armed robbers at the top. He was woken at night by guards knocking on his door, his food was laced with pieces of barbed wire, glass and "other unmentionable stuff".

For nearly nine years, he was detained in maximum-security prisons (the former Boggo Road Prison and Wacol Prison) before being transferred to a farm prison, "an open security area" where he could finally see more than 100 meters into the distance.

In the 14 years since his release from prison, Stafford has suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder but he says he is doing better now. He and Welsh love music (he used to be into Phil Collins, now it's more rap, "probably because I've got a bit of anger in me, I have to try to get it out in my music"), hanging out with their friends (they have a strong support group), travelling, riding their bikes and climbing mountains.

Stafford has never sought compensation because he has always said this was about truth more than money. "At some stage, if they just keep dragging it on the way they have, [it may be] the only way to drag it out of them is to put in for compensation." For him, one glaring question remains: Why is the savage killing of a child and the reopening of the investigation after his conviction was quashed "not in the public interest?"

Hailing from south-west France, Charlene completed a Master of Journalism and Communication degree at UNSW—Awarded with Excellence. She has a keen interest in feature writing, investigative and photo journalism. She also holds a Bachelor of Digital Project Management, loves the outdoor life, CrossFit, Vinyāsa & Ashtanga (yoga).