Australia closed its international borders exactly one year ago, at 9pm on March 20, 2020. In the first of a two-part series, Australian outbreak epidemiologist Mary-Louise McLaws runs her ruler over Australia's COVID report card and looks ahead to what it will take to "kill the pandemic".

The Australian vaccine rollout is underway, days go by with zero community transmission, even state borders are open again. The news from the SARS-CoV-2 frontline "feels" good.

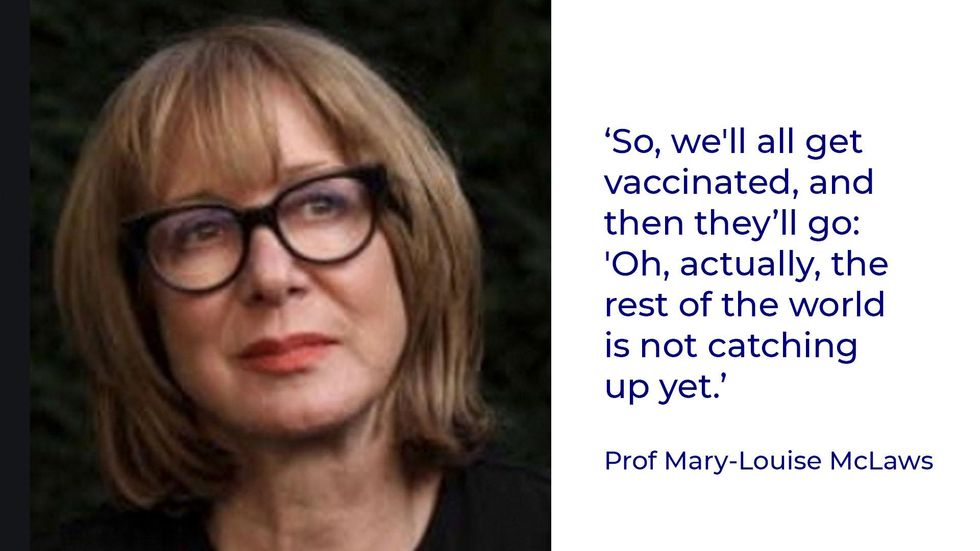

However, for world-renowned outbreak epidemiologist Mary-Louise McLaws, "facts, not feeling" are what matters when communicating COVID information and that has made her an essential voice on the pandemic for Australians.

"Regardless of how Australia is faring in comparison to other nations, the overall battle is far from over," the UNSW professor said. One year after the World Health Organisation declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic on March 11, 2020, she sat down (virtually) with Newsworthy to discuss where we are on the COVID-19 timeline with regard to a return to a pre-COVID normal and what the future might bring.

In the past year, McLaws has become a veteran of the COVID media spotlight, so, when she says the "battle against COVID is far from over and it is going to take a lot more than a vaccine to really kill this pandemic" it's a sobering reality check.

McLaws is well placed to interpret both international and domestic COVID developments. She is a member of the World Health Organization Health Emergencies Program Experts Advisory Panel for Infection Prevention and Control Preparedness, Readiness and Response to COVID-19 and a member of the NSW Clinical Excellence Commission COVID Infection Prevention and Control taskforce.

The hard-hit United Kingdom, United States and Europe are "nowhere near the beginning of the end", she said. In Europe, despite the beginnings of the vaccine rollout, there are concerns of a third wave; in the US, while infection and death rates have fallen dramatically since January, 1300 Americans are still losing their lives to the virus every day, with a jarring total of 540,000 deaths to date.

McLaws noted the bulk of the vaccine produced so far has been ordered by the United Kingdom and the United States, which means low and middle-income countries may have to wait until 2023 to receive the vaccine.

She said, in a bid to control the virus, the UK was "so desperate they are vaccinating every single person at least once" despite the protocol requiring two vaccines.

"I'm very concerned that they don't understand that global citizenship means that if they don't get this right, and that there are mutants in the viruses that then play out because they found the partially immune person, to then develop new mutations."

The crucial time window until middle and lower-income countries receive the vaccine could also allow new more infectious mutations to emerge. To prevent spread of mutated strains of the virus, she said "Australia should promote equitable vaccination of COVID-19 in developing countries to help them "begin their end".

"So, Australia, put your hand up for vaccinating Indonesia, or vaccinating Papua New Guinea," she said. "We need to start helping, and every other country."

This week's news from Australia's nearest neighbour underscores that need. In PNG, which had largely escaped the pandemic until now, the infection rate has spiked dramatically, leading to fears there is now widespread community transmission both in the capital Port Moresby and across the country. Australia has committed to send medical staff and an initial 8000 doses of the vaccine to immunise frontline workers.

Fresh mutations of the virus could create future challenges for countries and regions such as Australia that have got community transmission under control.

"The rest of the world have not been led by good global citizenship. Therefore, we're not really even at the beginning or at the end of the beginning. We could be, but when we open our borders ... we're opening [them] to the rest of the world who are still in the beginning of their fight," McLaws said.

''Dr Tedros [Adhanom Ghebreyesus], from WHO, constantly reminds us that we are in a global village, and that if we don't get it right with the rest of the world, we're just a single voice and we're not going to be singing into a choir if we're not globally responding.

"So we'll all get vaccinated, and then they'll go: 'Oh, actually, the rest of the world is not catching up yet'.

Even for those who have been vaccinated, said McLaws, in up to 25 per cent of cases the vaccine will not elicit an immune response. That has implications for Australians hoping to return to overseas travel and for a quarantine-free return home.

Suddenly, when you step back and review the international SARS-CoV-2 frontline, the news is not so "feel good".

"When we go overseas with our vaccine passport, what are they going to do with us when we get back? Because we could be one of those 25 per cent that come back with a variant. So, the community are not quite ready yet to hear that because they're so over hearing all the bad news."

McLaws said, going into the second year of the pandemic, it will require strong public messaging to carry public opinion. "To say, all right, we are at the end of the beginning, but we're going to help the rest of the world get to the beginning of their end. And the only way to do that is to share vaccines, and then we can really start to get back to normal."

— Additional reporting by Daphne Zhang

Part 2: Professor McLaws rates Australia's media on its pandemic coverage

Jessica is studying a double degree in Media (Communications & Journalism) and Arts (Sociology & Anthropology) at UNSW.