Marc Sidarous

Marc is a Master of Journalism and Communications student at UNSW and journalist at The Motley Fool. He has a passion for journalism and news with a keen interest in the media, politics, foreign affairs, and how they intersect in everyday life. If he's not acting dumb on Twitter, it's because he is being dumb in the real world. Some of his impressions are good, but many are not.

Comment

On July 15, 2020, The Australian newspaper published an exclusive story, sourced to Victorian health authorities, linking the recent Black Lives Matter protest in Melbourne to a COVID-19 outbreak in public housing towers in the city's north-western suburbs.

The story, "Coronavirus: Black Lives Matter protest linked to tower cluster" by journalist Rachel Baxendale, caused waves. Politicians and breakfast TV and radio hosts had for weeks been warning people "do not go, it's dangerous". Prime Minister Scott Morrison had chimed in, urging people against "importing things happening overseas to Australia". Baxendale's COVID-protest link story provided the proof detractors of the BLM movement "knew" was coming. They could rub it in the faces of smug lefties and woke hipsters.

One problem. While the story was narrowly accurate, the implied claim of a "direct link" between the BLM protest and the tower cluster story was bunk.

Over the course of Victoria's second wave lockdown, when Premier Daniel Andrew's daily news conference was essential viewing for homebound Victorians, Baxendale made a name for herself with her relentless approach. Question after question, each one a verbal dagger aimed straight at the premier's political aorta, looking for the kill.

The "Dan Stans" came to the premier's defence. A social media phalanx of die-hard Labor Party supporters, they were intent on protecting the premier at all costs. They became feral, attacking any and all things perceived as a threat to their messiah Dan. Baxendale was number one on their most wanted list.

Journalists, in turn, stepped in to defend her. Rita Panahi of News Corp's Herald Sun, Joe Hildebrand of news.com.au, Phil Coorey and Aaron Patrick of Nine's The Australian Financial Review and Chris Uhlmann of Channel Nine, all wrote pieces focussed on the problem of aggressive people of Twitter. Yet not one of these journalists examined the merits of her inflammatory claim of a link from the Black Lives Matter protest to the towers COVID cluster.

The Oxford Dictionary defines "link" as "a relationship between two things or situations, especially [italics added] where one affects the other". Baxendale's story does not claim a causal or direct link, (and indeed includes a quote from Victoria's Chief Health Officer Brett Sutton expressing scepticism the protesters caught the virus at the rally), but the way the story is framed – from the headline claim to the use of phrases "demonstrates clear links", "confirmed a link" and "confirmation of the link" in the body of the story – primes the casual reader to make that jump.

What the story finally reveals, is the link between the tower cluster and those who attended the BLM protest was a genomic one. The six separate COVID-positive cases who attended the protest, (with no evidence to suggest they acquired the virus at the protest), are "linked" genomically to the tower cluster in that they all contracted a virus that originated via the Stamford Plaza hotel quarantine leak.

Two days after the story was published, Vic Health issued this statement, attributable to a DHHS spokesperson, to media: "We are aware of six confirmed cases who attended the Black Lives Matter protest. Currently there is no evidence to suggest they acquired the virus from the protest. None of these cases are known to reside at a major public housing complex. Currently no known nor suspected episodes of transmission occurred at the protest itself."

Baxendale stands by her story, telling The Guardian on July 17 it was "meticulously researched and carefully written and the facts within it have not been disputed by [the Department of Health and Human Services Victoria]".

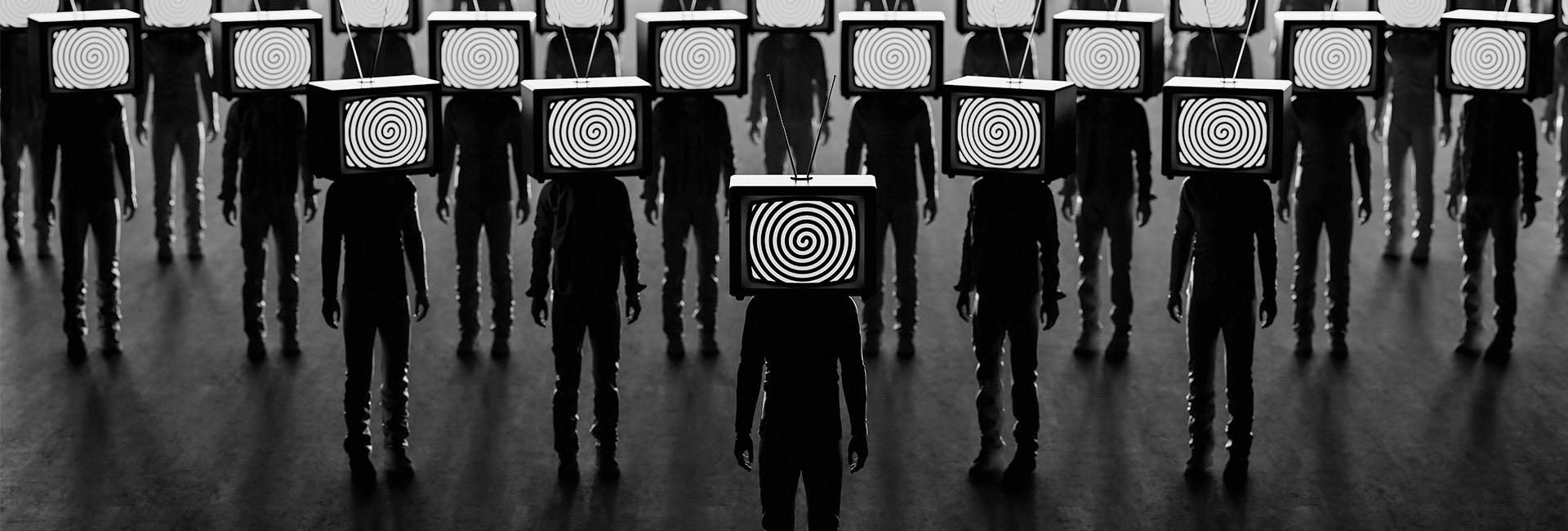

There is a flaw in Australia's media landscape. When journalists feel it is more important to challenge users of Twitter, Australia's eighth most popular social platform (behind LinkedIn and WordPress) than to assess their own failures, then we've entered "The Upside Down".

Former prime minister Kevin Rudd lays the blame squarely at the feet of Rupert Murdoch and he has at least 500,000 Australians who agree with him. He may be partly right, but the problems in Australian media don't respect corporate borders.

Jennine Khalik is a former journalist with The Australian, the ABC and Crikey. I went to meet her on November 4, election day in the US (AEDT). It was early. A quintessential spring morning. The drive to our meeting spot was a little far, so I put on KISS-FM with Kyle and Jackie 0. I listen to commercial radio, sue me!

Being the election and all, the breakfast power duo was speaking with Network 10's Hugh Riminton live from Washington DC with all the details on when/if results would come through. Their conversation turned towards the prospect of violence. A legitimate avenue to be sure, especially as the then President was a lightning rod for political extremism.

What does Riminton proceed to do? He succumbed to the media disease of both-siderism. Kyle and Jackie O took the bait. The allegedly omnipresent yet elusive Antifa movement was discussed in the same breath as the very real threat from Trump Patriots and the infamous Proud Boys. (The Antifa involvement claims were again spun in early reports from the deadly January 6 storming of the Capitol.)

Khalik and I met on the back patio of a cafe in Sydney's inner west. She was in all black. Mostly, there was some purple on the logo of her graphic t-shirt. She pulled out a noir, leather-bound notebook and a glass bottle of V energy drink.

"You can take the girl out of Granville. Ha-ha."

I asked her what drove her out of journalism.

"It was a cumulation of factors," she confessed. One incident she recalls vividly happened to a friend of hers, but it deeply affected Khalik's own perceptions of the industry.

According to Khalik, in 2019 a media outlet, that she chose not to name,

This story is just one of many she sees as illustrating the Australian media's "irredeemable" qualities. "The Australian media landscape is so tiny and so people are afraid of upsetting others. It's all built on ego and whether you toe a certain line."

Can it change?

"No," she said bluntly, then expanded. "It might change as a reaction to structural changes in Australian society but that's not going to happen for a very long time. When you still have Aboriginal people dying in custody and so many things that are so ... I guess intrinsic as a part of Australian values. If Australia can't even reckon with its past properly, and its present, then I don't think ... the media is just another pillar (of it)."

Khalik claimed the story on the alt-right was killed in the cradle, that it could never run in any mainstream outlet because they don't take issues of race and fascism seriously. The decision to spike came a year after the ABC ran an exposé on an almost identical story. The only difference being instead of the Young Liberals, it was the Young Nationals. Members were expelled, Nationals leadership went on the defensive and other media outlets followed up the ABC story.

As irritating as it can be to our lives and, more directly, to our narratives, there is always nuance and inconsistency to consider. I haven't been able to verify Khalik's story, but I have no reason to suspect fabrication. To be clear, it's not her only story of a negative interaction at work. There was the time she was excoriated in front of an entire newsroom for using the word "Palestine" in a story instead of Palestinian Territories, or when she was asked to dub over an interviewee's Arabic in a broken, Middle Eastern accent.

No one stood up for her.

For context, Khalik is the daughter of Palestinian refugees. For her, to be told her heritage was not real, that her people did not exist, nor had they ever existed was painful. "It's cultural genocide," she said to me, the pain seemingly as fresh that November morning as it was the day it was inflicted.

Palestine was designated a non-member observer state by the United Nations General Assembly in 2012. The ABC style guide instructs journalists not to refer to Palestine, rather it should be the Palestinian Territories. At the other end of the spectrum The Guardian tells its journalists to refer to the West Bank and Gaza as Palestine, not the Palestinian Territories.

This is where the nuance comes back into our conversation. The media is not a monolith, it's fragmented. Yet in saying that there is a perverse culture. A culture that stymies real conversation. A culture that doesn't capture the breadth of our continent.

As Jennine Khalik is pessimistic, Nance Haxton is optimistic. Haxton, who refers to herself as "The Wondering Journo", spent years working in rural and regional towns across Australia.

"I started in Port Augusta, then moved to Broken Hill. After that I moved to the Sydney newsroom, then Brisbane. Finally, I moved to Adelaide and worked for Radio Current Affairs."

She doesn't work for the ABC anymore, but she still considers herself a journalist through and through. Her passion for telling stories is obvious. It bursts out of her like a dam at capacity. These days, Haxton is the journalist-in-residence at Griffith University in Queensland and a part-time podcaster.

I couldn't meet her in person, due to COVID restrictions. So, we talked over Zoom. Even being thousands of kilometres apart, the chat felt more intimate than meeting at a cafe. I caught a glimpse, if fleeting, of "the real Nance". Unvarnished, at home and comfortable. Her desk is littered with a cacophony knickknacks and totems from differing aspects of her life. The sapphire-coloured globe, the artefacts from exotic lands, even the poster advertising the Primo Estate Winery in South Australia hung behind her - all reveal something about her person. Her dress matched both her personality and her office. A flowery number teeming with colour.

"Working in rural and regional Australia really exposes you to so many people whose lives you don't get to hear about usually. Working in media, especially, you get to meet so many interesting characters and share those stories with everyone. I loved working in country Australia, definitely.

"The stories I loved telling the most were of Indigenous Australians." She is genuine when she says this. You can hear it in her voice. Most people have a tell, for Haxton, her voice drops about half an octave when she is talking from her soul. She's followed this passion for Indigenous issues into her academic career, researching the history of blackbirding in Australia. Blackbirding was slavery, in essence. First Australians and Pacific Islanders were either tricked, or violently coerced into becoming slaves, mostly in mines or on agricultural plantations.

(A month or two before chatting with Haxton, blackbirding had made a rare appearance in the Australian media. Another salvo in Australia's never ending culture wars, with the Prime Minister proclaiming Australia had never been a slave nation. He later apologised, acknowledging "hideous practises" had occurred.)

I asked Haxton about her experiences of the inner workings of the newsroom. "Yeah, they are exciting places to work." I noticed the hesitation in her voice and asked for more detail, hoping to coax a more substantial response from her.

"Just lots of great and interesting people. Anyway, most of my career was spent in either extremely small newsrooms or just working on my own. When I lived in Broken Hill and Port Augusta, most of my time was spent meeting with and interacting with locals."

I changed tact, asking why she took on her new podcasting venture.

"I was made redundant and I wasn't done being a journalist," she said.

But what did "being a journalist" mean? Was there any pressure to kill stories, were there expectations about things you could and could not say? Things you might be able to say now, on your podcast?

"I didn't get that sort of pressure working at the ABC," Haxton replied. "It's not like working at a commercial network."

She is telling me at the ABC at least, stories don't get spiked. The pressures do exist, but they exist at other networks and newspapers, the ones reliant on advertiser dollars. This contradicted Khalik's recollection of events at the ABC.

So, I remind myself, there is nuance. The media is a spectrum of opinions. Just because it's skewed to one side, doesn't mean the other side doesn't exist. This would be true within media organisations, as well as in the wider media industry. Yes, on the one hand you have the old-school types. The ones that pretend they can be unbiased, which unwittingly allows bias to flourish. Yet, in the other, there are some glimmers of change.

Two examples come to mind. One is ABC data journalist Casey Briggs, who has recently focussed on coronavirus data trends. The data guides his coverage of the issues and he's not afraid to call out those that wilfully misrepresent it. The other is Business Insider Australia.

Their coverage of the Black Lives Matter movement in Australia, the proliferation of right-wing propaganda online, and the economic plight of younger Australians has been against the grain. No equivocation, no both-siderism, no mincing words.

The main problem with today's media seems to be the gatekeepers. A 2020 report initiated by Media Diversity Australia found that all but one of the top TV news executives in the country were white men. I am not being reductionist here. They are usually older and almost always come from backgrounds of either privilege or had connections. Being white and male does not ipso facto make you an unworthy news director. The problem is there are other voices being left out of the conversation.

Lisa Cox and Akashika Mohla both work for the Queensland chapter of Media Diversity Australia. Mohla is the Asian women's lead officer, while Cox is the disability affairs officer.

Mohla sees "a problem with diversity in Australian media, definitely

," she tells me matter-of-factly. "We see too often the faces and the voices don't match our Australian society. I am a South Asian woman. You are of Egyptian heritage," she said, drawing attention to me now. "How often do we see not just journalists, but people who work in PR and the media in general that reflect us?"Cox very much feels the same, but from the perspective of someone with a disability. "I've lived on both sides of it. My first 22 years I was perfectly abled and then I wasn't. You don't realise how much you take for granted when you're able bodied."

She and I had both just come from our respective gyms when we logged onto the Zoom call, she in Brisbane and me in Sydney. I bring this up because a little later on in our conversation Cox revealed a pet peeve.

"Inspiration porn. Do you know what that is? You see it all the time with disabled people and I really hate it. [TV news] will run a story about a disabled person who climbs Mount Everest and how inspirational it is – but for some disabled people, going to the shops is like their own Mount Everest, and you won't see that in the news."

I asked Cox why disabled people were underrepresented in broadcast media. Did she believe it to be systemic or was there only some minor adjustments that were needed?

"It's probably a bit of both," she replied. "Definitely there are systemic issues and there are also minor things too."

Are studios even designed for people who use a wheelchair? "It depends. Some do and try really hard to make accommodations and there are others that frankly don't. There's one example I can think of, where I went to a studio to shoot something … and to get in the building, there was a step. I was in my wheelchair and someone had to physically carry me."

We seem to be leaning towards systemic issues then.

So, acknowledging the media is not a monolith, you can still identify the problems in Australian media: it's insular, has strong gatekeepers and it's based on who you know more than what you know. This is leading to a fourth estate that does not reflect the depth of Australia's viewpoints, backgrounds (racial, economic, educational) and circumstances.

What's to be done?

One solution lies in bypassing the gatekeepers and the institutions, taking the side streets instead of the toll roads, or better yet, catching the bus. Andrew Law hopped on our metaphorical bus. He, along with Ben McLeay, Lucy Valentine and Theo Pengelly host and produce the Boonta Vista podcast. Their website describes the show as a "political" podcast for "smart" people (quotation marks included). Also, according to their website, they cover the important topics such as "What are those clowns in Canberra up to?", "Can nonna be used for military blast testing?" and, arguably most important of all, "Is Bigfoot circumcised?"

Law has a deep, baritone voice that, through biological processes not yet known to ear, nose and throat specialists, seems to cast its own echo. His beard is as thick as his voice is rich. A curly, voluminous beast not dissimilar to the facial hair captured in the sculptures of ancient Persians. His choice of fashion (a red and black plaid shirt) and background (bare white wall) for our Zoom call reflected his general demeanour. Not flashy, no filter, no varnish, just 100 per cent genuine cotton.

He is a family man. His day-job is in IT and graphic design, usually for the public service. He calls himself a socialist but he doesn't go on about it. As he told me, he avoids labels in general because "online leftists can be real dicks about it".

He met his co-hosts on Twitter. Pengelly is an engineer but Valentine and McLeay were both writers with already established audience followings.

On episode 174 of their podcast, they discussed the defeat of Donald Trump and the then President's false claims that the election was rigged. The episode's first third consists of mostly laughing at Trump and his lackeys in the Australian media, particularly Andrew Bolt of Sky News. It's a refreshing look at both politics and right-wing personalities.

"I don't think [the podcast] would be possible without Patreon," Law said of their paid subscription model. Boonta Vista eschews traditional revenue streams from corporate advertisers in favour of users directly paying for the content, raising approximately $6,000 a month. It's not enough to fund the show full time but enough to cover the basic costs.

So, how did the Boonta Vista team convince 1,271 generous souls to pay a monthly fee for the content and have many more people listen to the once weekly free episode? Law's answer is so simple but quite startling. "Ben and Lucy already had a large following. They brought a lot of people with them … I don't think we would have been able to succeed without it. The podcasting market is very saturated at the moment."

He's right. According to the website Podcast Insights, there are over 1.5 million shows available for download. As Law told me, "I don't think I would have the same passion for it if I made a podcast and only 10 people or so would listen. I mean, what's the point?"

McLeay and Valentine were writers before doing the podcast. Valentine in a freelance capacity and McLeay for Pedestrian. In other words, they were in media. They were born out of the ecosystem they are trying to subvert. It seems the gatekeepers cannot be evaded after all.

Nance Haxton, same thing. She has a podcast which generates about $2,000 a month. She told me most of her paying subscribers come from people who have followed her work for a long time. Jennine Khalik too has a podcast and a Patreon, her platform birthed by the media industry.

The most successful paid podcasts, blogs and online video services are all people who have either been in or are closely connected to the media or entertainment sphere. Not just in Australia but around the world, from Pulitzer Prize winner Glenn Greenwald to former stand-up comic, male model and current ALP foot soldier Jordan Shanks, aka Friendlyjordies.

If you don't start in media, the other way to grow your show is by inviting popular guests, preferably those who have their own podcast. As Khalik realised during our conversation: "You're at the mercy of these bigger players." Bigger players whom, more often than not, also got their start in the media world. So, if that's the case, if we can't escape the gatekeepers, what's the plan? Is there any hope or is Khalik right? Is Australian media doomed to repeat its failures?

I don't think so, and neither do Lisa Cox and Akashika Mohlah from Media Diversity Australia. We didn't just discuss the problems in Australian media but potential solutions too. A basic step would be for news directors and executive producers to interview more people for jobs, or in some cases, conduct interviews in the first place. They are encouraging organisations to make real inroads into the universities, the local papers and the community stations in their search for fresh talent.

"The talent is there," said Mohlah. "It's just waiting to be discovered." Cox wants journalists to notice the language they use.

"They keep saying I am 'confined' to my wheelchair but it's the opposite. The wheelchair gives me freedom, a park bench does not," she said. "Look, I could go on Twitter and tell journalists 'you're a f---ing idiot' all day long, but that won't achieve much. We're looking for solutions."

Podcasting may also be, despite concerns raised in this article, a good avenue for a greater range of voices in media. They may be sewn out of the same cloth as the traditional media, but in many cases, they chose to leave it because they rejected it. Yes, they are the "new gatekeepers", but they no longer have to deal with a news editor spiking their story idea at inception, they can relax the conditions of entry.

Even Khalik, when we talked about the Boonta Vista podcast, or outlets like Business Insider Australia and journalist Casey Briggs, admitted it wasn't 100 per cent doom and gloom.

"Yeah, I guess it can get better. We'll just have to wait and see."