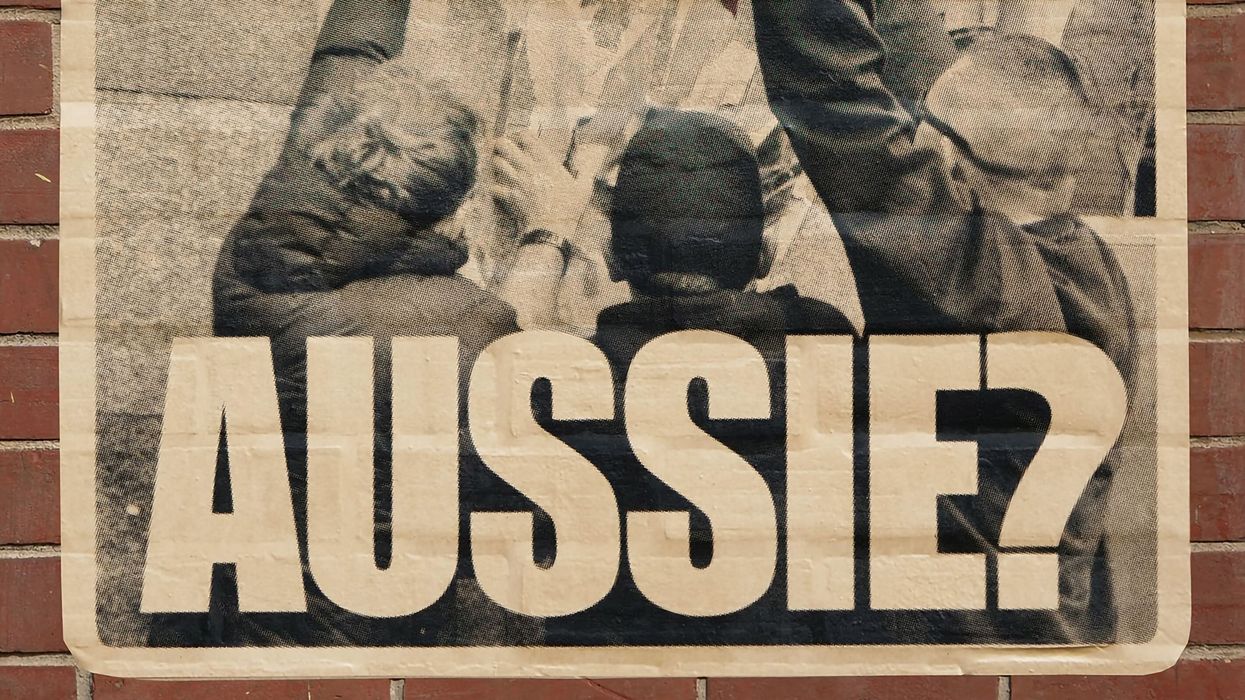

In August, thousands of people joined the anti-immigration March for Australia protests across the country. Many of those in the rally were young men.

In late August, after a morning swim at Sydney’s Victoria Park pool, I lay in the sun, soaking in the first hints of spring.

Those short, peaceful moments were interrupted by the faint sound of drums and chanting.

It grew louder and louder until the air cracked with that unmistakeable jarring chant: "Aussie, Aussie, Aussie! Oi, oi, oi!"

The March for Australia protesters had spilled from the city into Victoria Park. Soon, men draped in Australian flags were pressed against the pool’s fence.

I began filming, my body shaking, consumed by rage and fear. Trapped inside the pool, I was surrounded by a mob including self-proclaimed Nazis and white supremacists.

"Go back to China," one shouted.

"You should be glad we let you into our country," screamed another, as a police officer stood by watching.

When the crowd began to boo me, the officer turned to me, not them, and said I needed to step away because they had the "right to protest."

I am a 22-year-old Chinese-Australian woman. My dad grew up in Erskineville, the son of Chinese parents, one of which fled China in the late 1960s during the Cultural Revolution. My mum was born in regional Victoria.

I sent the footage to my friends. Underneath I wrote:

"I can’t believe how many guys our age are here".

Protectionist performances

Footage from the March for Australia rallies across the nation revealed one key detail: the overwhelming presence of young men.

Professor Steven Roberts, a sociologist at Monash University who researches youth and masculinity, says these marches weren’t simply displays of nationalism. They were performances of "hyper-traditional" and "protectionist" masculinity that is "central to right-wing rhetorics".

This is not new. Historically — from the 1934 Kalgoorlie Mines riots that saw 83 men convicted to the 2005 Cronulla riots that drew around 5,000 male attendees

— marches like this are largely made up of men coming together to vilify and intimidate those they deem as foreign threats.

Globally, it appears young men are becoming more conservative.

For example, during the 2024 US election, young male voters swung to the right more than they have in two decades, while in the 2024 UK election, young men were twice as likely as their female counterparts to vote for Nigel Farage's Reform party.

In Australia, while Gen Z are more progressive overall than previous generations at their age, more young men are voting conservative. Leading up to the 2025 federal election, 37 per cent of men aged 18–34 supported Liberal leader Peter Dutton, compared to 27 per cent of women, according to the November 2024 Freshwater Strategy Poll.

And during the 2022 federal election, just 19.8 per cent of Gen Z women voted Liberal, compared to 34 per cent of Gen Z men.

A crisis in masculinity

These right-wing movements thrive because they tap into what Roberts calls a "masculine deficit."

He says this sense of crisis leads some young white men to frame themselves as "uniquely oppressed", even though they are a historically privileged group. They view immigration, feminism and equality more broadly as a threat to "the role of white men and the imagined past they once had".

"They stimulate and bounce off a rhetoric of crisis, that men and masculinity are somehow in," Roberts says.

"The solution to that problem is to point at an ostensible other and say, ‘That's the problem over there.’

"It's a very seductive narrative […] particularly when there are broader social and economic tricky conditions."

Ryder Jack, a facilitator at Tomorrow Man, an organisation that teaches healthy masculinity, agrees.

"Boys are feeling under attack. They're feeling insecure … If you can't express emotion, if you always must prove or perform your masculinity […] guys feel really lonely and really lost," he says.

This idea that men are under attack feeds into the growth of the manosphere, an online echo chamber where misogyny, toxic masculinity and far-right ideology all intersect. Figures like self-proclaimed misogynist Andrew Tate prey on the grievances of some young men, transforming insecurity into resentment.

And with insecurities surrounding the cost of living through to shifts in gender dynamics, some young men are "retreating online for answers and for connection […] because the manosphere gives complex questions really simple answers", Jack says.

The manosphere relies on a language of crisis, says Roberts. Men are being attacked, women are selfish, and society is therefore collapsing.

Scapegoating immigrants

Inequality and the housing crisis are all feeding into this sense of crisis. However, as Roberts points out, protesters are "misdirecting anger at the wrong people."

Last year's Scanlon Foundation’s Mapping Social Cohesion Report found that nearly half of all Australians (49 per cent) now say immigration levels are "too high". This is up from 33 per cent in 2023.

In reality, net migration is declining. In 2023–24, migration fell to 446,000, down from 536,000 the previous year, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics

Australia’s housing crisis has been exacerbated by wealthy investors, not immigrants, Roberts says.

The Australian Institute has shown that 50 per cent capital gains tax and negative gearing encouraged investors to enter the housing market and allowed housing prices to soar.

And wealth and income inequality are rising in Australia, with the bottom quintile holding just 0.4 per cent of the total wealth while the top quintile holds 63.2 per cent, according to The Australian Institute.

"It’s manufactured outrage," Roberts says. They are being "animated and agitated by other actors who are telling them look over there" in the "wrong direction".

Isolation breeds discontent

Loneliness and disconnection is adding to the problem. According to the Mapping Social Cohesion 2024 Report, 62 per cent of Australians aged 18–24 report feeling isolated at least some of the time.

"Probably deep down [these young men] crave community and crave connection. In these online spaces, they think they're getting that community," Jack says.

He says many feel "rejected" by "left-wing" or "woke culture", pushing them toward reactionary online spaces that validate anger.

"Lots of young women are disconnected as well. But their reaction to these things is often internal rather than externalising," says Roberts.

Women tend to build community through "book clubs and knitting clubs and crafting clubs, those kinds of things where you can actually be not resentful but just produce productive outcomes for yourself".

By contrast, "men also build community, but [some] build community in violent and aggressive ways […] through resentment and through a sense of dissatisfaction".

"It’s about difference and blaming the other […] that lead to people being on the street and protesting."

Misguided masculinity

"There's a logic amongst these groups that you have to point to particular people that have stolen your privilege that have taken what is rightfully yours," Roberts says.

According to Jack, the masculinity the manosphere preaches is about "blame".

"I think it's an easier road to take, blaming others rather than looking internally, asking yourself critical questions […] that might be what's feeding more guys coming to those kinds of events," he says.

The chants in Victoria Park were not just about borders, they were also about masculinity, power and belonging.

Until society confronts the loneliness driving young men toward reactionary politics, they will continue to feel entitled to scream at young women like me.

As I filmed, a fellow pool-goer, horrified by the protesters, shouted at one of them, "Where’s your girlfriend, mate?"

The young man was speechless and his puffed-out chest instantly deflated. He had nothing to offer in response, except to flick us the bird. Amid all the racist noise, it was that jab that cut him the deepest.

That moment crystallised it all for me.

Related stories

Rose is a third year student studying Media (Communications and Journalism) & Arts at UNSW. She is interested in politics and pop-culture, and is particularly passionate about highlighting diverse and marginalised voices in her writing.