His unmistakable posters emblazoned with the word Aussie have attracted global attention. But for Adelaide artist Peter Drew, topics like national identity and belonging still need more discussion

Artist Peter Drew has been wrestling with the word Aussie. The word is emblazoned across the top of his distinctive posters, which have been spotted on city walls in Adelaide, Sydney, and Melbourne, over the last decade. It’s an easy nickname, a light-hearted label; but it’s also a term that's loaded, territorial and endlessly contested.

For Drew, what began as a simple art experiment has become an evolving project about identity, belonging and the unstable line between art and politics. He didn’t expect the poster project to follow him for ten years, but he recognised early that it would spark a reaction. "I knew it would be popular. I knew it would be provocative. These are questions playing out not just in Australia, but across the world," he says.

Now he's returning to the project, and in January 2026, he'll start travelling across Australia to put up 1,000 posters that will have a series of new faces.

The appeal of street art

The Adelaide-based artist took to street art after learning about it from a housemate. Street art was appealing because of its independence, being able to display art publicly and reach an audience directly, without intermediaries like galleries or the traditional art world, and initially Drew's work was mostly apolitical stencils and paste-ups.

He was living in Scotland, pursuing his master’s degree at the Glasgow School of Art, when his viewpoint shifted. Being an Australian abroad during the 2013 federal election with its "stop the boats" rhetoric made him reflect on what it means to be Australian.

He began to pursue more political projects, as he observed the audience's appetite for such work, even though he says there are limits: "I think art loses something when it does pursue politics."

"And so, it has to be done in a way which sort of balances that or draws attention to that exchange. So yeah, I guess those were the things I was thinking about when I started the Aussie posters," he says.

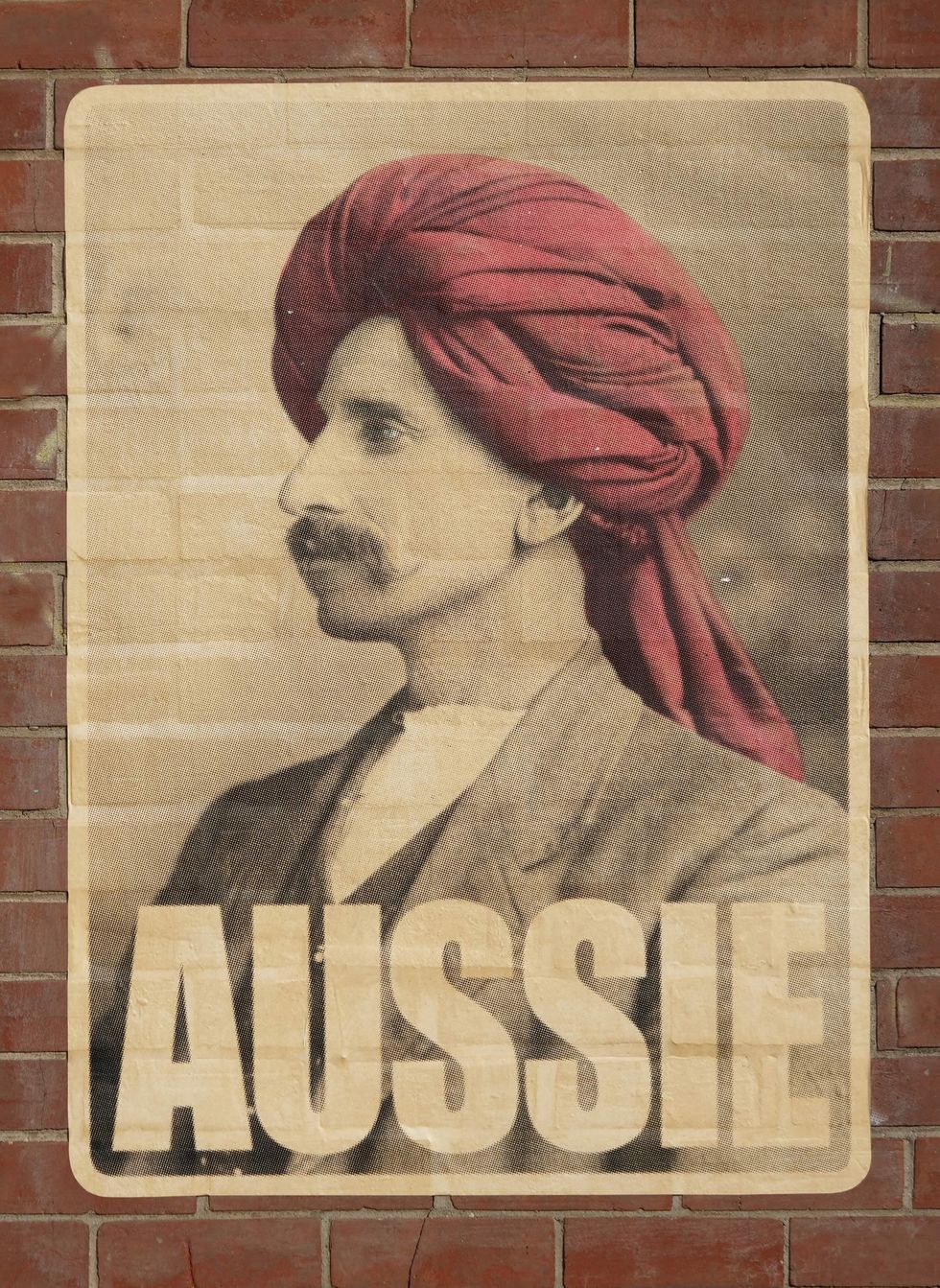

Back home after graduating, he was searching through the National Archives when he came across a series of historical portraits of migrants from the era of the White Australian Policy.

These black and white portraits showed those who had applied for exemption from the dictation tests that were part of the policy. These tests were designed to block non-white individuals from immigrating to Australia, and they were so challenging that no one passed between 1909 and 1958. Non-white Australians who were living here and who wanted to travel abroad had to apply for an exemption certificate from the test, as they knew they couldn't pass it and avoid deportation.The White Australia policy was enacted in December 1901 and the final remnants removed in 1975.

"There's a tension in the posters: they can be read as suggesting that this person is Australian, or that the White Australian policy defines what it means to be Australian," Drew says.

"This paradox is why I chose those images. I believe art often serves as a redemptive space, where people can explore spiritual notions like redemption more safely than in politics. For example, many Australians, including myself, look back at the White Australian policy and feel it doesn't represent how I see Australia as more than just a racially exclusive concept. There's a desire to redeem or reinterpret that past."

His first poster was a portrait of Monga Khan in 2016, displayed in Adelaide.

Drew chose this image because Monga Khan looks heroic and the photo resembles a regal portrait. He also selected Monga Khan because Khan was Muslim, and the work was in response to the increase in Islamophobia after the 2014 Lindt Cafe siege and the circulation of various ISIS videos.

The power of pranks

Drew's new series of Aussie posters finish with a question mark. He decided to add this after seeing three people tear down his posters after a March for Australia rally in Adelaide in August.

He says he felt the ambiguity that had always been implied should be made explicit. He explains that the question mark nudges viewers toward the tension in his work, namely who gets to be Aussie? And who believes they can decide? And he believes street art is meant to be confronting and unavoidable, to compel passersby to have a reaction. Occasionally he meets those who are hardened in their views, uninterested in dialogue, and for him, the only option is to step away and leave.

In October, he included a simple prank within an Adelaide poster: anyone trying to peel it off would have water spill onto them. Mischief has become a part of his work. "If they’re attacking the posters. It reveals something in themselves," he says.

He'll continue to use pranks occasionally, when he can see their value. He says he’s observed that aggressive counter-protests to anti-immigration sentiment can escalate conflicts and draw more attention to any rallies. Instead, satire and ridicule can diffuse tension. And particularly in Australia, a sense of irreverence makes this approach effective.

He is equally aware of how those on the left interact with his work: "When it comes to political art, the left really enjoys political art through the imagined discomfort of a less progressive person." That imagined discomfort becomes a part of the appeal.

Drew doesn’t agree with this self-congratulatory pleasure, not because the interpretation is wrong but because it risks turning the artwork into a moral victory lap.

"I think it's regrettable because the artwork becomes a tool for self-congratulatory tendencies on the left. I want to find a way to discourage that in the people who enjoy my posters."

Art vs propoganda

Drew wants people on all sides of the political divide to question themselves. He sees this as the difference between art and propaganda.

"Propaganda instils political certainty without self-reflection and discourages doubt. Art, by contrast, encourages questioning assumptions and seeking common ground with opponents, preventing polarisation that ultimately benefits the right in the long term," he says.

He adds that art offers opportunities for reflection. For example, for those Australians who want to acknowledge the horrors committed in the name of the White Australia policy. "I believe that through art, people have a redemptive impulse, viewing art as a suitable arena for exploring spiritual concepts like redemption."

He’s pleased when the posters create a sense of connection. "That curiosity is powerful because it connects one person on the street with another on the poster, moving beyond abstract political concepts about race and identity. It becomes just two individuals."

Unresolved feelings

Ten years on from the appearance of that first poster, Drew says the questions remain unresolved .

"All I have are unresolved feelings. About what being an Aussie means. I don't have any resolved feelings about it at all. And I don't expect to have any resolved feelings at the end of it."

He doesn’t believe Australia is heading toward a post-racial utopia. At best, he thinks the project only creates small, temporary pockets of peace and belonging for those who see them.

For Drew, connecting with others and navigating emotions to quell fear and foster connection gives the work meaning, even though some are increasingly hardened to the issues. "Sometimes, you find someone who is just going about their day or, if saturated in these topics, has an agenda to harm others and avoid dialogue. The ideal is meeting someone who's afraid but open to having their concerns heard and addressed productively."

What frustrates him about the way young people get involved in politics is the spiritual longing for purity and utopia that often comes with it. He sees this longing as harmful because it shows discomfort with one’s own flaws and mortality.

Instead he believes art should evoke doubt and questioning, not certainty. And that art and artists should be separate from politics. He believes politics can distort art's purpose by imposing a seriousness that stifles curiosity and openness. And he hopes to offer audiences seeking certainty something different.

For young Australians grappling with the meaning of the word Aussie, he has some advice. "[It's] connected to tradition, but it is also open to reinterpretation and change. My goal is to use images that acknowledge our past without fear, demonstrating that through imagination we can grow and shape our identity for the future."

He describes art as a positive creative act that collaborates with the audience. "I see it as a hopeful, constructive process, not about expelling problematic racist elements. I prefer to build a positive identity and invite people into it rather than confront or attack others."

And he reserves the right to prank those who interfere with his posters: "I believe [these] are friendlier acts, more playful than hostile. In the current debate, I think using a bit of ridicule can be more effective."

Related stories

Sanjana is completing a Master of Journalism and Communication at UNSW. She's drawn to stories at the intersection of politics, gender and culture and believes in journalism that refuses passive language and holds power to account. When she's not reporting, she's baking, shooting on film and finding a good playlist for walks on the beach.