- Andre was named 2020 Walkley Student Journalist of the Year (All Media) for his two-part series on Rwanda – 'The dark side of Africa's poster child' and 'Who wins when Rwanda plays the 'genocide guilt card'

ANALYSIS

It's 25 years since ethnic genocide tore Rwanda apart. In 1994, "the land of a thousand hills" wasn't on any tourist's bucket list. Today, more than a million international visitors make the trip each year: to commune with the mountain gorillas and to pay their respects at the genocide memorials scattered across the country.

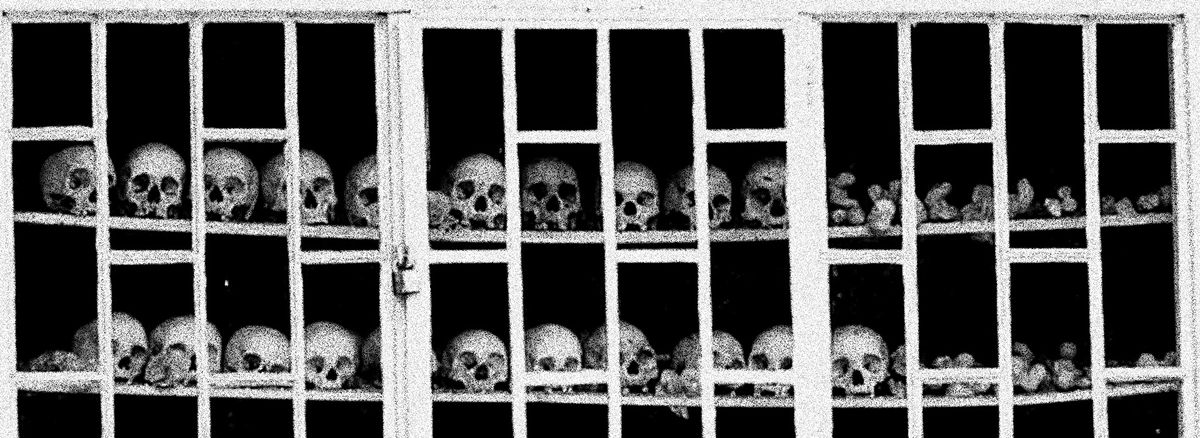

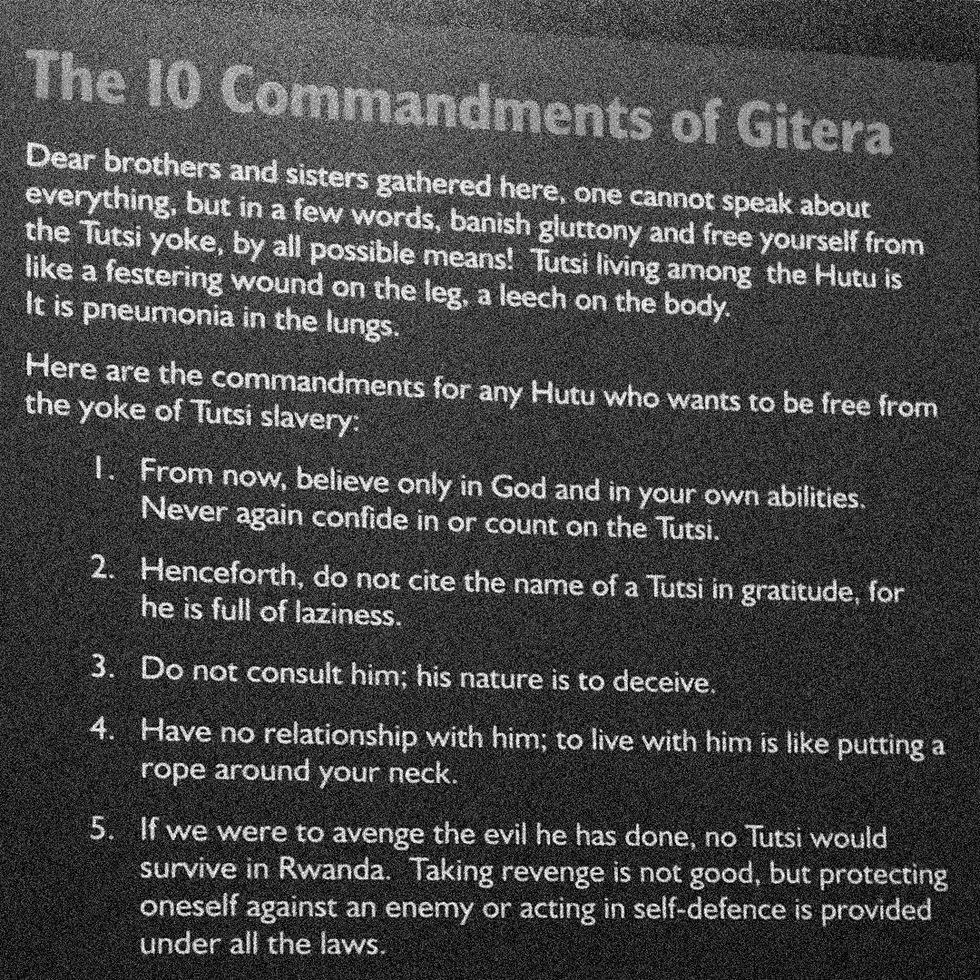

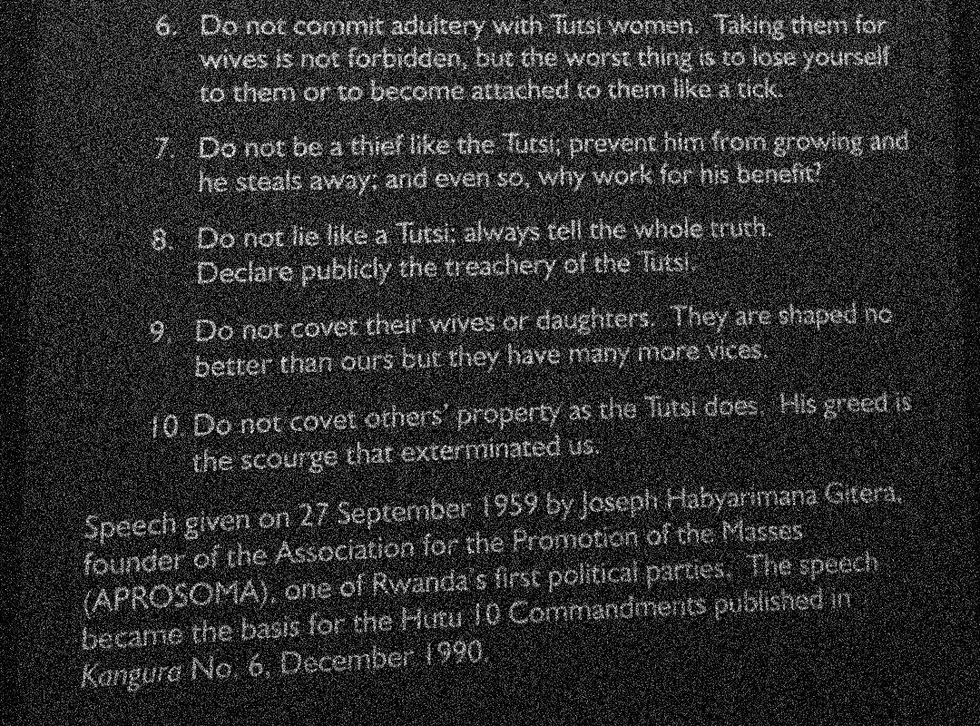

In the Murambi Genocide Memorial Centre in southern Rwanda, they'll see the mummified corpses of Tutsi genocide victims, including children; in the capital Kigali, they'll read the pro-Hutu propaganda posters describing the Tutsi ethnic group as "cockroaches" and hear genocide survivors, still living with trauma, tell their personal stories.

On the surface, the primary message associated with these memorial sites is one of reconciliation and looking forward, the preferred government narrative. But Hutu victims of the genocide (and those killed in post-genocide violent reprisals), are ignored.

Beneath the narrative of "reconciliation and looking forward" lies a powerful subtext: the failure of the international community to halt the violence which raged for 100 frenzied days, killing up to 1 million; and the role of French military in arming and training the Hutu Interhamwe militia who were the primary genocide aggressors.

For international visitors, a visit to these memorials evokes profound sorrow, but also guilt.

Critics of the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) government say this is no accident, that it is using and aggravating this guilt for its own political purposes, that it is playing the "genocide guilt card" on the international community.

"The card is basically to say to internationals 'you failed us, we stopped the 1994 genocide, you did nothing'," says Dr Susan Thomson, a Canadian academic specialising in post-genocide governance in Rwanda. "So, therefore, we are going to build Rwanda in our vision, you can give money to that vision or you can get out of the country."

'Look, if you don't pull yourself together we'll have another genocide, and you know what that means.'

There have been many reports, by academics, media and government agencies, in the years since the genocide, as to why there was no intervention by the international community. In 2004, even Hollywood weighed in, with the film Hotel Rwanda, dramatising the events and portraying "the West" as an uncaring bystander to the slaughter. It has left a deep well of collective guilt within the international community.

Some believe that collective guilt is now leveraged by the Rwandan government to evade scrutiny as it strengthens its increasingly authoritarian position. Thomson says it has led, post 1994, to the Rwandan state receiving "vast sums of unconditional foreign aid".

And those dollars keep rolling in. A 2018 World Bank shows Rwanda's foreign developmental aid per capita dwarfs that of its four neighbouring states. The OECD reports the country received more aid money from 2010-2017, than it did in the decade in which the genocide occurred.

Thomson acknowledges the flood of money is in part due to the outcomes foreign donors have seen. "[Rwanda's president] Kagame can, with this volume of money, actually build the things that donors want to see: they want to see high school education, they want to see reduced maternal health liabilities."

For Kagame, who has been in power since the genocide, the guilt card works on two fronts, with international aid donors and domestically, where he has used the threat of another genocide to suppress the Rwandan populace.

He does not speak of it in his English-language speeches, but in Kinyarwandan, the country's official language, "he'll chastise and he'll really condescend to people in different communities to say 'look, if you don't pull yourself together we'll have another genocide, and you know what that means," says Thomson, who is fluent in Kinyarwandan.

Those who speak out against the government's strategy in modern-day Rwanda risk being denounced as "genocide deniers" and criminalised by Rwanda's legal system, according to Human Rights Watch's 2018 World Report. In recent years, Rwanda has imprisoned those who oppose government narratives and practices, including opposition political candidates such as Diane Rwigara, using the charges of "genocide ideology" and "ethnic divisionism".

Dr Filip Reyntjens, an emeritus professor at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, says the country "is a volcano". The government risks stoking the very ethnic divisionism it says it is trying to avoid by commemorating only the Tutsi victims, and ignoring the hundred of thousands of Hutu victims of RPF violence (in Rwanda and the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo).

"Let's turn a blind eye to massive human rights abuse, let's forget about all the people that have been killed by the RPF, let's look for stability now not just in Rwanda but in the region too. But that is a short-term consideration," says Reyntjens.

The West's new willingness to overlook Kagame's autocratic ways, (fuelled in part by collective guilt over its non-response to the genocide), while pouring money into the country, may create a new cocktail of ethnic dissent.

"If something akin to mass violence happens in Rwanda," Thomson says, "we absolutely must look into the international community for complicity."

Again.