Experts are concerned about the impact of rising cancer cases because the Australian health system is already under pressure due to an ageing population and a burnt out workforce.

Australia is seeing an alarming increase in cancer diagnoses in people aged in their 30s and 40s.

According to a government report released in October, there's been a 14 per cent increase in cancers diagnosed in the 30-39 age group, while the 40-49 age group saw an increase of 33 per cent.

The AIHW report shows prostate, colorectal, pancreatic and thyroid cancers are the most significant contributors to the increase. And Australia now has the highest incidence of colorectal cancer in people under 50 in the world.

Reasons for the increase are not definitively known. According to the Australian Journal of General Practice, lifestyle factors, such as diet and physical activity, and genetic factors, including family history of cancer and gut microflora diversity, are contributors.

Doctors and scientists warn this trend is likely to continue and say more funding for research, diagnosis and treatment is urgently needed.

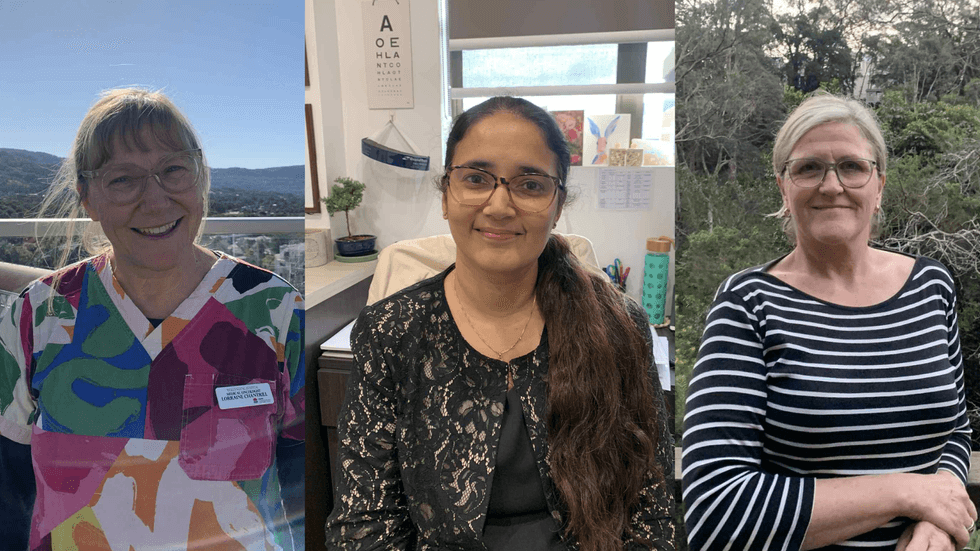

Prof Lorraine Chantrill, a senior medical oncologist in the Illawarra Shoalhaven local health district, is very concerned.

"At the moment, New South Wales Health Service is very ill prepared for this," she says.

"One of the organisations I work with, the Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group, is focusing on early onset bowel cancer and getting funding and philanthropy to fund programs that specifically look at bowel cancer in younger people because that's a tsunami coming."

Early onset, late diagnosis

While case numbers are rising, receiving a diagnosis can be challenging due to poor understanding of the trend.

For example the latest National Bowel Cancer Screening Program Monitoring Report showed that less than 14 per cent of those diagnosed with potential gastrointestinal cancer cases receive diagnostic colonoscopies within the recommended 30-day window in 2023. This was due to high patient numbers, inefficient referral processes and even over-testing. In regional areas, some patients wait up to 179 days after a positive bowel screening test for their procedure.

Bowel Cancer Australia ambassador Rachel was 38 when she was diagnosed with stage three bowel cancer.

"It doesn’t discriminate", she says.

She says her stomach cramp symptoms were initially dismissed by her GP as constipation. It wasn’t until she was admitted to hospital for severe bloating almost a year later that she was referred for a colonoscopy.

"They think it’s an old person disease", she says.

This assumption can inform everything from low rates of early detection to insufficient government fund allocation.

A cancer diagnosis at this life stage can disrupt everything. For example Rachel had three children under the age of ten when she began treatment, and she says found it challenging.

"You’ve got a family, you’ve got a mortgage, you might not have savings. It’s a different stage of life to be thrown into that chaos," she says.

While patients undergoing treatment may be eligible for federal income support programs like Jobseeker or the Disability Support Program, there is a lack of awareness about patient entitlements from healthcare professionals and patients. Unfortunately Rachel did not qualify for government funding.

And, although some cancer patients under fifty may draw from their superannuation under severe financial hardship, permanent incapacity, a terminal medical condition, or to pay for unpaid expenses, she was unable to withdraw from her superannuation early either.

"There’s just no support really", she says.

Individual approach

Dr Puja Mehrotra, a medical practitioner at East Corrimal Medical Centre, says educating GPs and patients is an important part of catching early onset cancer before it can progress.

"Sometimes we get stuck in our ways," she says. "When we look at young people, we really don't think about cancer as the first differential diagnosis."

But Dr Mehrotra says simply lowering the screening age for different cancers may not be a silver bullet.

Certain cancer detection tests like mammograms are designed for older bodies, and could therefore produce false negatives.

She is also concerned that over-testing and over-treating could result in increased levels of anxiety among patients.

She says an individualised approach is needed instead. "A lot of the time the patient knows their body a lot better than [we do], so taking them seriously is really important."

"If you think that there is something going on in your health, definitely go talk to your GP," she says.

Supporting health care workers

In July 2025, the federal government announced the Cancer Australia Research Initiative, committing $7 million towards research into early onset cancers.

Prof Chantrill describes this as "a drop in the ocean."

She says it reflects a trend of the government funding research and resourcing only after healthcare services are under extreme pressure.

The increase in cancer patients is putting more pressure on cancer health workers, who are already coping with high patient and administrative loads.

An oncology study released last year showed high rates of burnout and low job fulfilment in trainee and consultant medical oncologists.

"It’s very taxing," says community health nurse Vicky Carlisle, about the emotional toll of nursing young terminal cancer patients.

She says overall nursing conditions need to improve to attract more people to the workforce to address the prospective nursing shortage as cancer patient numbers increase.

"A lot of people don’t want to go into nursing now, because it’s hard work and the pay’s not that great," she says.

But there are some helpful initiatives in place.

For example, New South Wales Health recently expanded their provision of Hospital in the Home, which provides care and monitors patients’ vital signs while they remain in their homes. Ms Carlisle says this helps to minimise congestion in hospitals.

The initiative also offers nurses more freedom, even though this is less cost efficient than traditional hospital care and the initiative is less accessible in other states.

Prof Chantrill says the medical culture needs to change to attract new talent to help treat and prevent cancer.

"We, as leaders in the profession, need to listen to what young people need as part of their work life balance … and create jobs that satisfy all that."

Raising awareness

Cancer is still predominantly a disease of the elderly and younger people have significantly better outcomes from cancer diagnoses.

"Young people can handle the really intensive treatment and treatments for them can be quite successful," Prof Chantrill says.

Yet she says young people need to think of cancer as something that could affect them and address preventable risk factors, like poor diet and sedentary lifestyles.

And there are signs the increase in cancer diagnoses could result in more research funding.

Prof Chantrill believes this will lead to more medical breakthroughs, but the human cost for patients and their families remains "untenable".