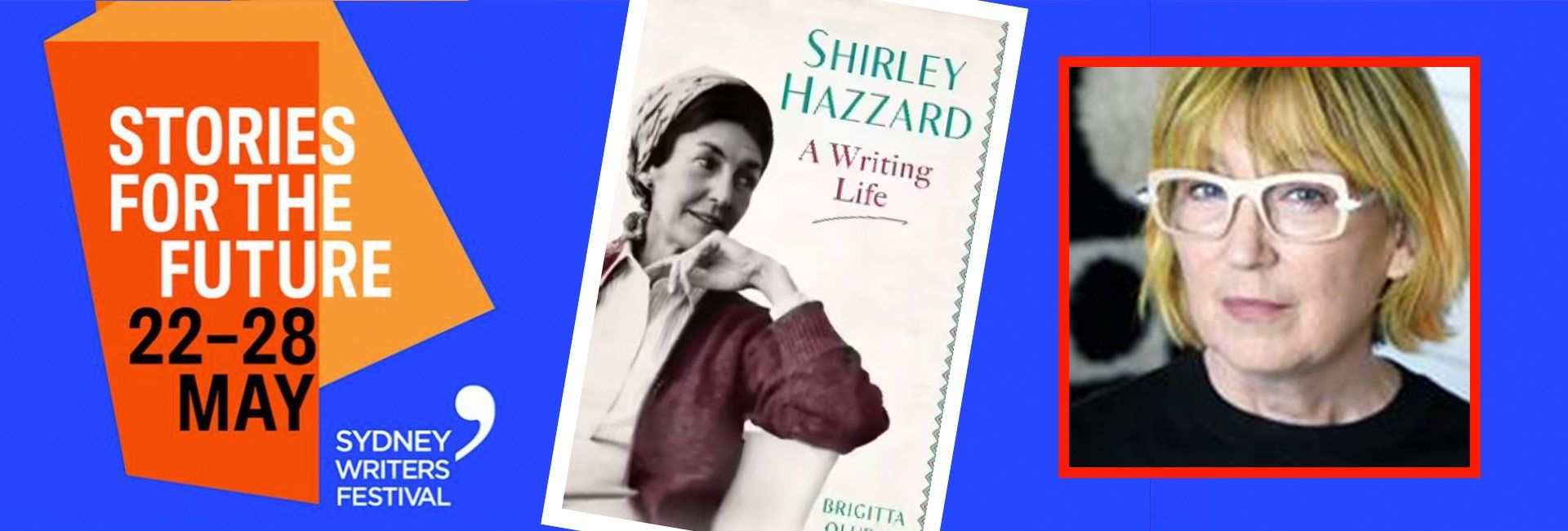

Newsworthy speaks to author and academic Brigitta Olubas on getting to know her subject, her process for writing the biography Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life and letting go of the need for a punchy title.

Who is Shirley Hazzard to you? Is she an Australian novelist or an Australian expatriate novelist or a novelist first and foremost?

I came to Shirley Hazzard first of all as an Australian writer. When I first read The Transit of Venus not long after it came out I was transfixed that someone could write about Australian life as a serious and beautiful thing; as if it mattered. This was new to me – I had come across it in Patrick White’s writing, but this felt somehow closer, and I was hooked. Then what kept me reading and writing about her work was simply its brilliance, in particular the gloriousness of her sentences – witty, beautiful, serious. No one else writes like her and, to follow one of her ideas about the relations between readers and writers, that paying her work attention was a form of respect for it, a kind of praise.

Would you like to introduce yourself?

I teach in the English and Creative Writing program in SAM at UNSW. I write about and teach Australian literature, diasporic writing and writing by migrants and refugees. I feel incredibly privileged to have had a secure academic position for several decades – I think teaching and writing about literature is the best profession anyone could possibly have and I begin each day of teaching or writing or reading with real excitement.

What drew you initially to her work? What has compelled you to write so extensively on her and her work?

I haven’t just been writing about Shirley Hazzard. Since publishing my monograph in 2012 I’ve edited two books of her non-fiction and short fiction and another book of scholarly essays about her work. But I’ve also co-edited two books about other writers (Elizabeth Harrower and Antigone Kefala) and many essays and book chapters on other writers, most particularly about Behrouz Boochani’s No Friend But The Mountains. I’ve kept going back to Hazzard’s work partly out of a sense of scholarly responsibility, and also because her executors were very keen for me to write her biography. Her work is rich and complex and repays close and sustained attention (10 years isn’t really so long in academic life).

She once wrote that art was the only afterlife of which we have evidence. I love that.

What aspect of Hazzard’s life or writing informs your own work?

Shirley Hazzard’s life was nothing like mine, I’m glad to say. But I’ve been compelled by the way she always insisted on taking herself, and her writing seriously, even while she was overlooked or dismissed (particularly by Australian critics, and this despite the praise her work received overseas). And I’m also inspired by her insistence on the importance and authority of poetry, of literature – that feels so rare and necessary these days. She once wrote that art was the only afterlife of which we have evidence. I love that.

Did your perception of Hazzard change across the process of writing her biography?

I hadn’t been very interested in her life before I wrote – she seemed simply to have been privileged and fortunate. What I found was that her life and self were as complex as anyone else’s, and that meant that her story was a lot more interesting than I’d imagined.

Did you read biographies often before you started writing this biography?

I rarely read biographies before agreeing to take this one on, I didn’t really see biography as important or interesting – how I’ve changed my mind. I read a number of them before I started writing, but the ones I admired (Sylvia Townsend Warner’s of TH White, Hermione Lee’s of Penelope Fitzgerald, Richard Ellman’s of James Joyce) were all really different from each other, so I can’t say they informed my writing in any particular beyond making it clear that I needed to create an engaging story about someone’s life, to give a sense of her inner as well as her outer life while respecting the mystery of all lives lived. And of course they corrected my sense about biography not being an interesting or important genre.

Has working on a biography changed the way you see your own life?

That’s a strange thing to consider. I suppose yes and no – her life was so profoundly different from mine in almost every respect. At the same time, writing the book did connect my life to hers in some profound ways: as I began work on it in 2018, my younger sister died, suddenly and unexpectedly. And then last year, just after I had sent back the page proofs, my older sister died. So the writing of it was very much washed by my own losses, my own grief. There is a thread of melancholy that runs through all her novels, and I think my own experiences were making me even more attentive to that. Also writing about her losses and grief – friends, her husband – through her later years while in our world we were all dealing with COVID sharpened all that for me too.

What was the process for obtaining permission from Hazzard’s estate?

Shirley Hazzard’s executors and her publisher were very keen for me to write the biography because they were impressed by the scholarly work I’d done on her. That was important – the sense they gave that the work of literary scholarship was valued and that it could, even should, inform the authorised account of her life.

What was it like to be so immersed in her life and have access to her archives?

Yeah, the immersion was a bit challenging! Her archives weren’t processed, so it was a jumbled of unsorted boxes, some of which I’d looked at and photographed years before, and couldn’t go back to as I had to do all the research on short trips to the US. I ended up with 38,000 photos on my phone, almost all of which were the archival material I used to write the book (mobile phones have revolutionised archive work!) So just in a practical sense, it was pretty unwieldy and taxing.

On top of that, as always with archives, there was too much information – in all senses. As you can imagine, people tend to be prolix rather than restrained in diaries and letters, and there were a lot of repetitions of the same kinds of events or thoughts or even the same actual events and thoughts. But I had to read them all before deciding which ones to incorporate and which to leave out, which made for long intensive days. And there was also “too much” in the sense of things I didn’t need to know, too intimate, sometimes embarrassing. There were many such moments, and all biographers comment on how complex it is to work with archives for that reason. It’s kind of necessary thing, as biography itself is a genre that works itself between the private and the public, but finding the right place to be in that shuttle is going to be different for each biography and each biographer.

What was the process for choosing the title, Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life?

The title was really difficult. I had assumed that I would find the title in one of Hazzard’s own phrases, that I’d stumble on it while I was writing the book and re-reading her books. Her prose is so poetic I thought it would be easy to come up with something. But the opposite was true. Any phrases I found, once I took them out of their original context, were just flat or banal. And I realised that this must have been because the heart of Hazzard’s writing is the sentence, not the phrase. Michelle de Kretser kept texting me asking if I’d found a title yet. I kept sending her ideas I’d had, and she just kept saying No. Over and over, just No. (It became quite funny.)

In the end my publisher suggested what ended up being the title – he said he felt the book was strong enough to stand on its own, without a gripping title. (Interestingly, back when I was interviewing people, a NY writer I spoke to said: You better come up with a catchy title, because people have forgotten who she was.)

It seems an enormous task, putting together a person’s biography. You had glowing reviews from The New York Times, Wall Street Journal and The Guardian. At what point did you think, this is where I can stop writing it? Did you begin with a fixed end point, or did it shift over time?

Thank you – yes, the reviews have been lovely, and it’s been wonderful to see so many wonderful critics writing about her work again, also seeing new readers discover her work, including younger writers. I feel very proud that my work has contributed to that revival of interest in her. Deciding when to stop had a lot to do with publishing deadlines. I signed the contract to do the biography in late 2017, started doing intensive archive work in mid-2018 (I had to wait until I could get back to the US to do most of it, but I did have quite a lot of material I’d gathered over the years as I was doing the earlier work on her), and started writing at the start of 2019.

I discovered important new material – notebooks and diaries – in late 2019 after I’d written about a third of the book, so I had to go back and retro-fit some of the new material, so that slowed things down, and then in March 2020 I was in the US again doing a last pass through some archives when COVID hit, so I had to cut that trip short and dash home before the border closed, then wait for those archives to open up again in 2021, so that was a further delay. I finished writing in early 2022 and spent much of last year working on copy-edits and proofs, which is an intensive process but incredibly valuable, having excellent editors helping to refine the prose.

What is it like to be asked to talk about her? How much preparation do you undertake to talk about her? For example, do you read your own book on her?

It’s great to be invited to talk about the book and I’ve been blessed to have wonderful interlocutors at all the events I’ve done so far. For the first couple of podcasts I did a lot of re-reading and made piles of notes and then didn’t even look at them. I’ve lived in the book for so long that I found I had responses without really thinking. And thank you for your interest in this book, it’s a pleasure to be able to respond to such thoughtful questions. I hope the interview prompts people to think about reading her work – I’d recommend The Transit of Venus, her greatest novel, as the one to start with. It’s demanding but hugely rewarding.

A final question: Of all the Australian writers today, whose work most resembles Hazzard’s?

Shirley Hazzard is really a sui generis writer – she didn’t/doesn’t fit into established categories and her novels were each very different to each other, so it’s difficult to think of writers whose work might “resemble” hers. That said, two of the Australian writers working today I most admire are Michelle de Kretser and Fiona McFarlane, and they are both great admirers of Hazzard’s work. And there are points of connection: de Kretser uses sharp satire in some of the same ways and she also shares with Hazzard a real interest in people’s everyday working lives; McFarlane is an extraordinary conjurer of particular places and of characters’ perceptions, something Hazzard also did brilliantly, although quite differently.

And all three are wonderful writers of place and location; all of them give us flashes of insight into a larger world.