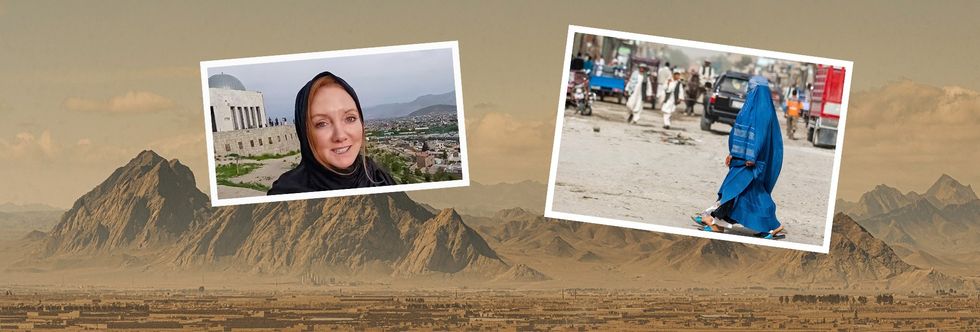

More than four years ago, the Taliban banned girls from attending secondary school. This generation of Afghan women knows the opportunities they are being denied.

"I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own," Audre Lorde

My grandmother was a midwife, my grandpa was an architect.

Their education saved their lives, and my own.

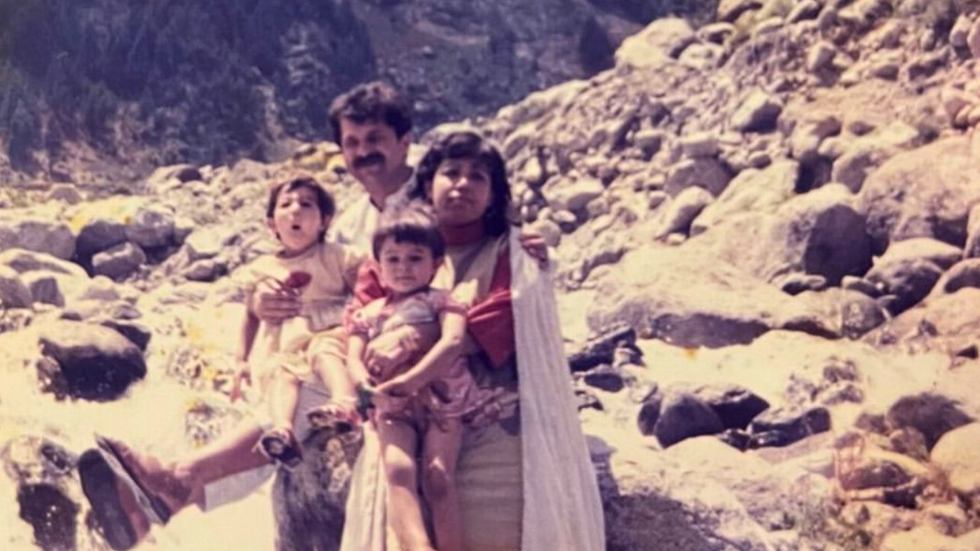

My maternal grandparents fled Afghanistan after the Soviet invasion in 1982. They had the means to pay a people smuggler to help them escape and their lives changed overnight. My mum left on the back of a donkey accompanied by rockets and hovering helicopters.

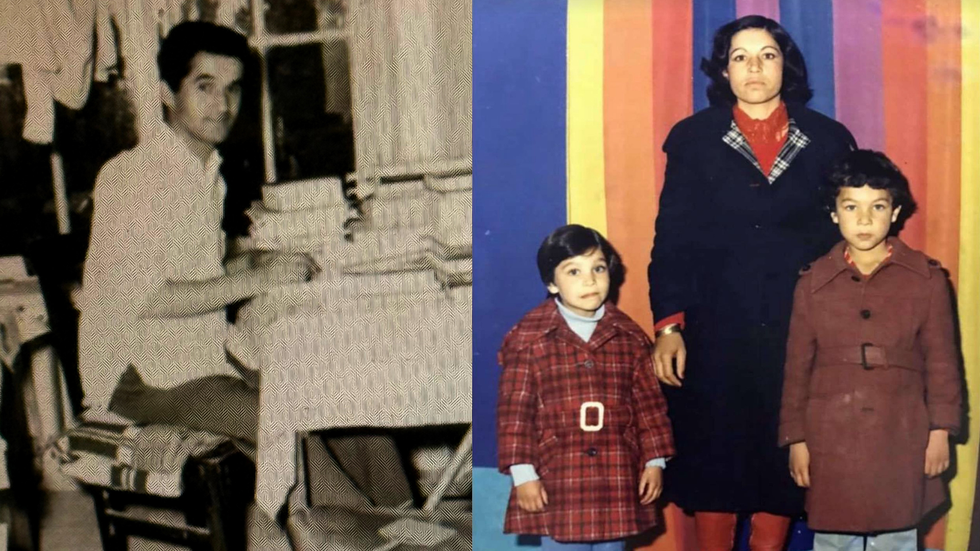

My father left in 1981 when he was seven years old. His father was a journalist who had fled the Communist regime in 1979 in fear of his life, and he arranged for his son to be smuggled into Pakistan where he would meet him. His mother remained in Afghanistan to look after his siblings, while the young boy posed as a stranger's son. He hid in the back of a truck for two days with little food or water.

Being captured meant certain death.

I absorbed my family's stories as if they were bedtime ones. But these weren't fiction, they were facts. Education was not just their escape route, but their entry ticket into Australia, as their sponsorship visas came from those they knew through their work.

Then in August 2021, the Taliban took control of Afghanistan.

It's scary to imagine where I'd be now if my family didn't leave the country. What would my reality be?

The likelihood is I'd be living under a regime that would have silenced my voice before I could speak up.

360/VR video: Seeing the women of Afghanistan do what they can to be educated - YouTube youtu.be

A 'struggle' others wish for

I've grown up in the quiet Sydney suburb of Castle Hill, where most people aren't thinking about the Taliban or the human rights they take for granted.

I've had books, school uniforms and excursions. Whenever I complained about early mornings or exams, I would be reminded of the journey my parents had to get an education.

"Don't take it for granted. This is 'struggle' someone else wishes for," my mum would say, drilling this into me from a young age.

When the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan, all the rights women fought for during the 20 years of US intervention fell apart.

Both my mother and grandmother watched in shock, overwhelmed by sadness that the progress women had made since they'd left had been snatched away.

Now, it is a country where the leaders tell women to stay home unless their job cannot be filled by a man's existence. The Taliban has taken away basic human rights and stripped women of any form of educational or societal development.

The last time a girl entered a secondary school classroom in Afghanistan was almost 1,500 days ago.

It's been more than four years since half the country's population was disenfranchised.

And unlike their mothers who grew up in the 1990s, this generation of Afghan girls knows the opportunities an education could give them.

The Taliban takes control

The Taliban emerged in the early 1990s in northern Pakistan, following the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. The Islamic militia group came out of the splintering of the Mujahadeen rebel group, and it was funded by Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

The promise made to the Afghan people by these men was that, once in power, they would restore peace to the country after decades of war, but they would also enforce Islamic law. They then introduced punishments in line with their own strict interpretation of Sharia law, including public stoning.

In 2001, they were removed from power by US-led forces, but slowly regained strength.

Then, on 15 August 2021, the Taliban declare an interim Afghan government, after the collapse of the security forces and the withdrawal of international troops.

360/VR video: My grandmother and I going through photo albums of images from Afghanistan - YouTube youtu.be

Since then, all progress has been reversed in Afghanistan. More than 2.2 million Afghan girls no longer attend school, according to UNESCO. The 2023 World Economic Forum says the country is the worst place in the world to be a woman. The World Economic Forum reports that globally women are still 123 years away from achieving total gender equality – but in Afghanistan, who's counting?

Pushed out of the public eye

In October 2021, I began volunteering with Afghan refugees who had just arrived in Australia. I met more than 100 people and ran English classes. Initially, the women were hesitant to attend my classes.

Many were fearful that there were spies who would report back to the Taliban. For some, their post traumatic stress weighted heavily and they didn't want to leave their rooms; others didn't want to attend because the classes were co-ed.

Our lives were very different, but we were united through language, culture and a deep sense of grief. Most had witnessed bombings and killings, others had left family members behind. A few girls said they were lucky to be in Australia as they had to burn their university degrees before escaping.

Their stories are the reality of thousands of women and girls in Afghanistan. It could also have been mine.

When the Taliban took control in 2021, the international community were quick to condemn. Now four years later, those voices have quietened. The sanctions and diplomatic isolation haven't changed the fact that Afghan girls remain locked out of school.

Afghan women have been resisting and they continue to do so – but with little support. Some underground schools still run in secret, but at great risk.

The restrictions have only grown even harsher. Women have been pushed out of the public eye. Even speaking in public is considered a crime.

And being a girl in Afghanistan means your future would be decided for you.

Your classroom is your kitchen, and your uniform is a burqa.

This is not religion, it's gender apartheid.

An uncertain future

The future for women in Afghanistan is uncertain, and the next generation is at risk, but forgetting them isn't an option. Silence is complicity, and moving towards gender equality cannot be global unless Afghan women are included.

What is needed is more consistent advocacy and political pressure to support these women.

There needs to be increased awareness, not just in hashtags or headlines, but by demanding that girls' education be non-negotiable. And the voices of those fighting back must be amplified.

People often tell me how "lucky" I am, and I don't disagree. But that word overlooks the perseverance of generations who resisted. My family's journey wasn't luck, it was risk. It was education.

I'm a proud Australian, but Afghanistan remains close to my heart. It's the language I use to communicate with my grandparents; it's the grief that lingers in my mother's stories; it's the pride I see on my dad's face when I speak about it.

I carry their exile in my body and with it, their hope.

My message for all students is not to take education for granted. Your readings are someone else's forbidden text. Your ambitions are someone else's death sentence. The spot you occupy in a university or school is a spot that a girl across the other side of the globe would give anything to have.

There's a Farsi saying: nah omaid nashaid. It means "don't give up hope".

I cling to this saying, knowing that Afghan women do too.

Related stories

Sabrine is studying a double degree in Media and Social Science. She is interested in what goes on in war-torn countries and is passionate about preventing human rights abuse. Her favourite novel is Paulo Coelho's The Alchemist and she enjoys reading historical fiction novels, especially those by Khaled Hosseini.